Software Architecture and Design

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

What should we consider when designing software?

How can we make sure the components of our software are reusable?

Objectives

Understand the use of common design patterns to improve the extensibility, reusability and overall quality of software.

Understand the components of multi-layer software architectures.

Introduction

In this episode, we’ll be looking at how we can design our software to ensure it meets the requirements, but also retains the other qualities of good software. As a piece of software grows, it will reach a point where there’s too much code for us to keep in mind at once. At this point, it becomes particularly important that the software be designed sensibly. What should be the overall structure of our software, how should all the pieces of functionality fit together, and how should we work towards fulfilling this overall design throughout development?

It’s not easy come up with a complete definition for the term software design, but some of the common aspects are:

- Algorithm design - what method are we going to use to solve the core business problem?

- Software architecture - what components will the software have and how will they cooperate?

- System architecture - what other things will this software have to interact with and how will it do this?

- UI/UX (User Interface / User Experience) - how will users interact with the software?

As usual, the sooner you adopt a practice in the lifecycle of your project, the easier it will be. So we should think about the design of our software from the very beginning, ideally even before we start writing code - but if you didn’t, it’s never too late to start.

The answers to these questions will provide us with some design constraints which any software we write must satisfy. For example, a design constraint when writing a mobile app would be that it needs to work with a touch screen interface - we might have some software that works really well from the command line, but on a typical mobile phone there isn’t a command line interface that people can access.

Software Architecture

At the beginning of this episode we defined software architecture as an answer to the question “what components will the software have and how will they cooperate?”. Software engineering borrowed this term, and a few other terms, from architects (of buildings) as many of the processes and techniques have some similarities. One of the other important terms we borrowed is ‘pattern’, such as in design patterns and architecture patterns. This term is often attributed to the book ‘A Pattern Language’ by Christopher Alexander et al. published in 1977 and refers to a template solution to a problem commonly encountered when building a system.

Design patterns are relatively small-scale templates which we can use to solve problems which affect a small part of our software. For example, the adapter pattern (which allows a class that does not have the “right interface” to be reused) may be useful if part of our software needs to consume data from a number of different external data sources. Using this pattern, we can create a component whose responsibility is transforming the calls for data to the expected format, so the rest of our program doesn’t have to worry about it.

Architecture patterns are similar, but larger scale templates which operate at the level of whole programs, or collections or programs. Model-View-Controller (which we chose for our project) is one of the best known architecture patterns. Many patterns rely on concepts from Object Oriented Programming, so we’ll come back to the MVC pattern shortly after we learn a bit more about Object Oriented Programming.

There are many online sources of information about design and architecture patterns, often giving concrete examples of cases where they may be useful. One particularly good source is Refactoring Guru.

Multilayer Architecture

One common architectural pattern for larger software projects is Multilayer Architecture. Software designed using this architecture pattern is split into layers, each of which is responsible for a different part of the process of manipulating data.

Often, the software is split into three layers:

- Presentation Layer

- This layer is responsible for managing the interaction between our software and the people using it

- May include the View components if also using the MVC pattern

- Application Layer / Business Logic Layer

- This layer performs most of the data processing required by the presentation layer

- Likely to include the Controller components if also using an MVC pattern

- May also include the Model components

- Persistence Layer / Data Access Layer

- This layer handles data storage and provides data to the rest of the system

- May include the Model components of an MVC pattern if they’re not in the application layer

Although we’ve drawn similarities here between the layers of a system and the components of MVC, they’re actually solutions to different scales of problem. In a small application, a multilayer architecture is unlikely to be necessary, whereas in a very large application, the MVC pattern may be used just within the presentation layer, to handle getting data to and from the people using the software.

Addressing New Requirements

So, let’s assume we now want to extend our application - designed around an MVC architecture - with some new functionalities (more statistical processing and a new view to see a patient’s data). Let’s recall the solution requirements we discussed in the previous episode:

- Functional Requirements:

- SR1.1.1 (from UR1.1): add standard deviation to data model and include in graph visualisation view

- SR1.2.1 (from UR1.2): add a new view to generate a textual representation of statistics, which is invoked by an optional command line argument

- Non-functional Requirements:

- SR2.1.1 (from UR2.1): generate graphical statistics report on clinical workstation configuration in under 30 seconds

How Should We Test These Requirements?

Sometimes when we make changes to our code that we plan to test later, we find the way we’ve implemented that change doesn’t lend itself well to how it should be tested. So what should we do?

Consider requirement SR1.2.1 - we have (at least) two things we should test in some way, for which we could write unit tests. For the textual representation of statistics, in a unit test we could invoke our new view function directly with known inflammation data and test the text output as a string against what is expected. The second one, invoking this new view with an optional command line argument, is more problematic since the code isn’t structured in a way where we can easily invoke the argument parsing portion to test it. To make this more amenable to unit testing we could move the command line parsing portion to a separate function, and use that in our unit tests. So in general, it’s a good idea to make sure your software’s features are modularised and accessible via logical functions.

We could also consider writing unit tests for SR2.1.1, ensuring that the system meets our performance requirement, so should we? We do need to verify it’s being met with the modified implementation, however it’s generally considered bad practice to use unit tests for this purpose. This is because unit tests test if a given aspect is behaving correctly, whereas performance tests test how efficiently it does it. Performance testing produces measurements of performance which require a different kind of analysis (using techniques such as code profiling), and require careful and specific configurations of operating environments to ensure fair testing. In addition, unit testing frameworks are not typically designed for conducting such measurements, and only test units of a system, which doesn’t give you an idea of performance of the system as it is typically used by stakeholders.

The key is to think about which kind of testing should be used to check if the code satisfies a requirement, but also what you can do to make that code amenable to that type of testing.

Exercise: Implementing Requirements

Pick one of the requirements SR1.1.1 or SR1.2.1 above to implement and create an appropriate feature branch - e.g.

add-std-devoradd-viewfrom your most up-to-datedevelopbranch.One aspect you should consider first is whether the new requirement can be implemented within the existing design. If not, how does the design need to be changed to accommodate the inclusion of this new feature? Also try to ensure that the changes you make are amenable to unit testing: is the code suitably modularised such that the aspect under test can be easily invoked with test input data and its output tested?

If you have time, feel free to implement the other requirement, or invent your own!

Also make sure you push changes to your new feature branch remotely to your software repository on GitHub.

Note: do not add the tests for the new feature just yet - even though you would normally add the tests along with the new code, we will do this in a later episode. Equally, do not merge your changes to the

developbranch just yet.Note 2: we have intentionally left this exercise without a solution to give you more freedom in implementing it how you see fit. If you are struggling with adding a new view and command line parameter, you may find the standard deviation requirement easier. A later episode in this section will look at how to handle command line parameters in a scalable way.

Best Practices for ‘Good’ Software Design

Aspirationally, what makes good code can be summarised in the following quote from the Intent HG blog:

“Good code is written so that is readable, understandable, covered by automated tests, not over complicated and does well what is intended to do.”

By taking time to design our software to be easily modifiable and extensible, we can save ourselves a lot of time later when requirements change. The sooner we do this the better - ideally we should have at least a rough design sketched out for our software before we write a single line of code. This design should be based around the structure of the problem we’re trying to solve: what are the concepts we need to represent and what are the relationships between them. And importantly, who will be using our software and how will they interact with it?

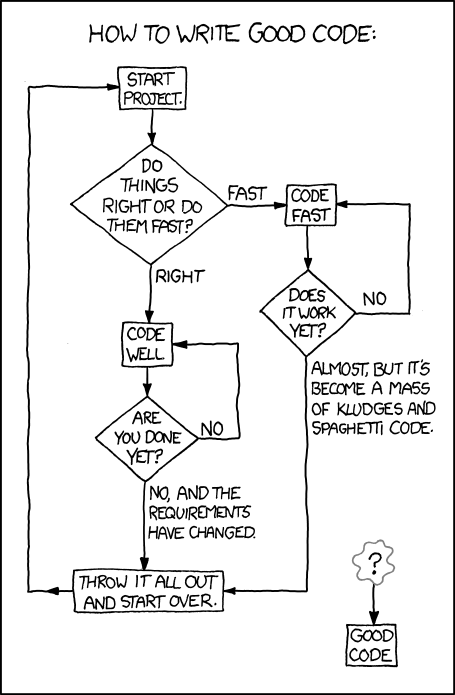

Here’s another way of looking at it.

Not following good software design and development practices can lead to accumulated ‘technical debt’, which (according to Wikipedia), is the “cost of additional rework caused by choosing an easy (limited) solution now instead of using a better approach that would take longer”. So, the pressure to achieve project goals can sometimes lead to quick and easy solutions, which make the software become more messy, more complex, and more difficult to understand and maintain. The extra effort required to make changes in the future is the interest paid on the (technical) debt. It’s natural for software to accrue some technical debt, but it’s important to pay off that debt during a maintenance phase - simplifying, clarifying the code, making it easier to understand - to keep these interest payments on making changes manageable. If this isn’t done, the software may accrue too much technical debt, and it can become too messy and prohibitive to maintain and develop, and then it cannot evolve.

Importantly, there is only so much time available. How much effort should we spend on designing our code properly and using good development practices? The following XKCD comic summarises this tension:

At an intermediate level there are a wealth of practices that could be used, and applying suitable design and coding practices is what separates an intermediate developer from someone who has just started coding. The key for an intermediate developer is to balance these concerns for each software project appropriately, and employ design and development practices enough so that progress can be made. It’s very easy to under-design software, but remember it’s also possible to over-design software too.

Key Points

Planning software projects in advance can save a lot of effort and reduce ‘technical debt’ later - even a partial plan is better than no plan at all.

By breaking down our software into components with a single responsibility, we avoid having to rewrite it all when requirements change. Such components can be as small as a single function, or be a software package in their own right.

When writing software used for research, requirements will almost always change.

‘Good code is written so that is readable, understandable, covered by automated tests, not over complicated and does well what is intended to do.’