Python Code Style Conventions

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

Why should you follow software code style conventions?

Who is setting code style conventions?

What code style conventions exist for Python?

Objectives

Understand the benefits of following community coding conventions

Introduction

We now have all the tools we need for software development and are raring to go. But before you dive into writing some more code and sharing it with others, ask yourself what kind of code should you be writing and publishing? It may be worth spending some time learning a bit about Python coding style conventions to make sure that your code is consistently formatted and readable by yourself and others.

“Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand.” - Martin Fowler, British software engineer, author and international speaker on software development

Python Coding Style Guide

One of the most important things we can do to make sure our code is readable by others (and ourselves a few months down the line) is to make sure that it is descriptive, cleanly and consistently formatted and uses sensible, descriptive names for variable, function and module names. In order to help us format our code, we generally follow guidelines known as a style guide. A style guide is a set of conventions that we agree upon with our colleagues or community, to ensure that everyone contributing to the same project is producing code which looks similar in style. While a group of developers may choose to write and agree upon a new style guide unique to each project, in practice many programming languages have a single style guide which is adopted almost universally by the communities around the world. In Python, although we do have a choice of style guides available, the PEP 8 style guide is most commonly used. PEP here stands for Python Enhancement Proposals; PEPs are design documents for the Python community, typically specifications or conventions for how to do something in Python, a description of a new feature in Python, etc.

Style consistency

One of the key insights from Guido van Rossum, one of the PEP 8 authors, is that code is read much more often than it is written. Style guidelines are intended to improve the readability of code and make it consistent across the wide spectrum of Python code. Consistency with the style guide is important. Consistency within a project is more important. Consistency within one module or function is the most important. However, know when to be inconsistent – sometimes style guide recommendations are just not applicable. When in doubt, use your best judgment. Look at other examples and decide what looks best. And don’t hesitate to ask!

As we have already covered in the episode on PyCharm IDE, PyCharm highlights the language constructs (reserved words) and syntax errors to help us with coding. PyCharm also gives us recommendations for formatting the code - these recommendations are mostly taken from the PEP 8 style guide.

A full list of style guidelines for this style is available from the PEP 8 website; here we highlight a few.

Indentation

Python is a kind of language that uses indentation as a way of grouping statements that belong to a particular block of code. Spaces are the recommended indentation method in Python code. The guideline is to use 4 spaces per indentation level - so 4 spaces on level one, 8 spaces on level two and so on. Many people prefer the use of tabs to spaces to indent the code for many reasons (e.g. additional typing, easy to introduce an error by missing a single space character, accessibility for individuals using screen readers, etc.) and do not follow this guideline. Whether you decide to follow this guideline or not, be consistent and follow the style already used in the project.

Indentation in Python 2 vs Python 3

Python 2 allowed code indented with a mixture of tabs and spaces. Python 3 disallows mixing the use of tabs and spaces for indentation. Whichever you choose, be consistent throughout the project.

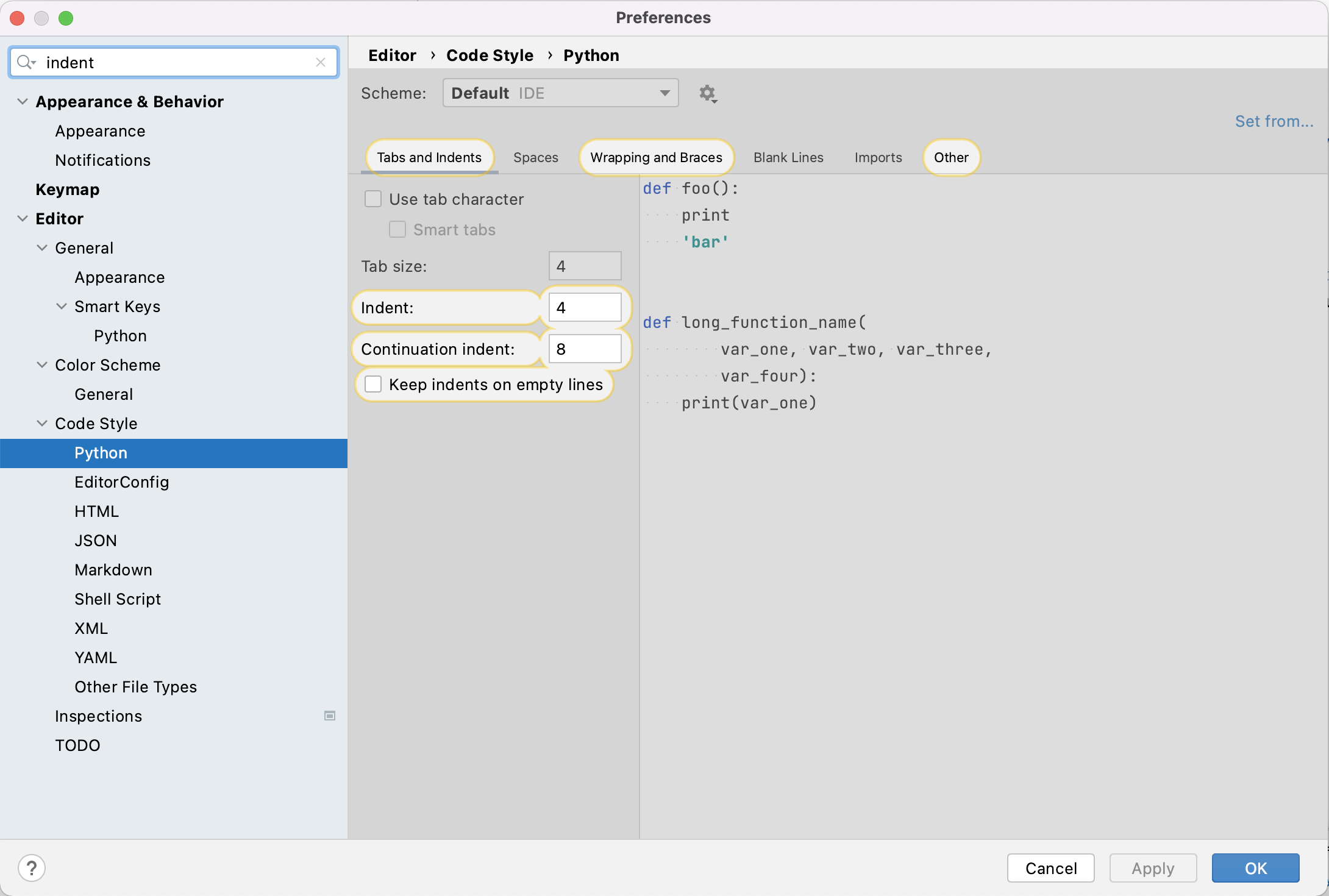

PyCharm has built-in support for converting tab indentation to spaces “under the hood” for Python code in order to

conform to PEP8. So, you can type a tab character and PyCharm will automatically convert it to 4 spaces. You can control

the amount of spaces that PyCharm uses to replace one tab character or you can decide to keep the tab character

altogether and prevent automatic conversion. You can modify these settings in PyCharm’s

Preferences>Editor>Code Style>Python (MacOS/Linux) or Settings>Editor>Code Style>Python (Windows).

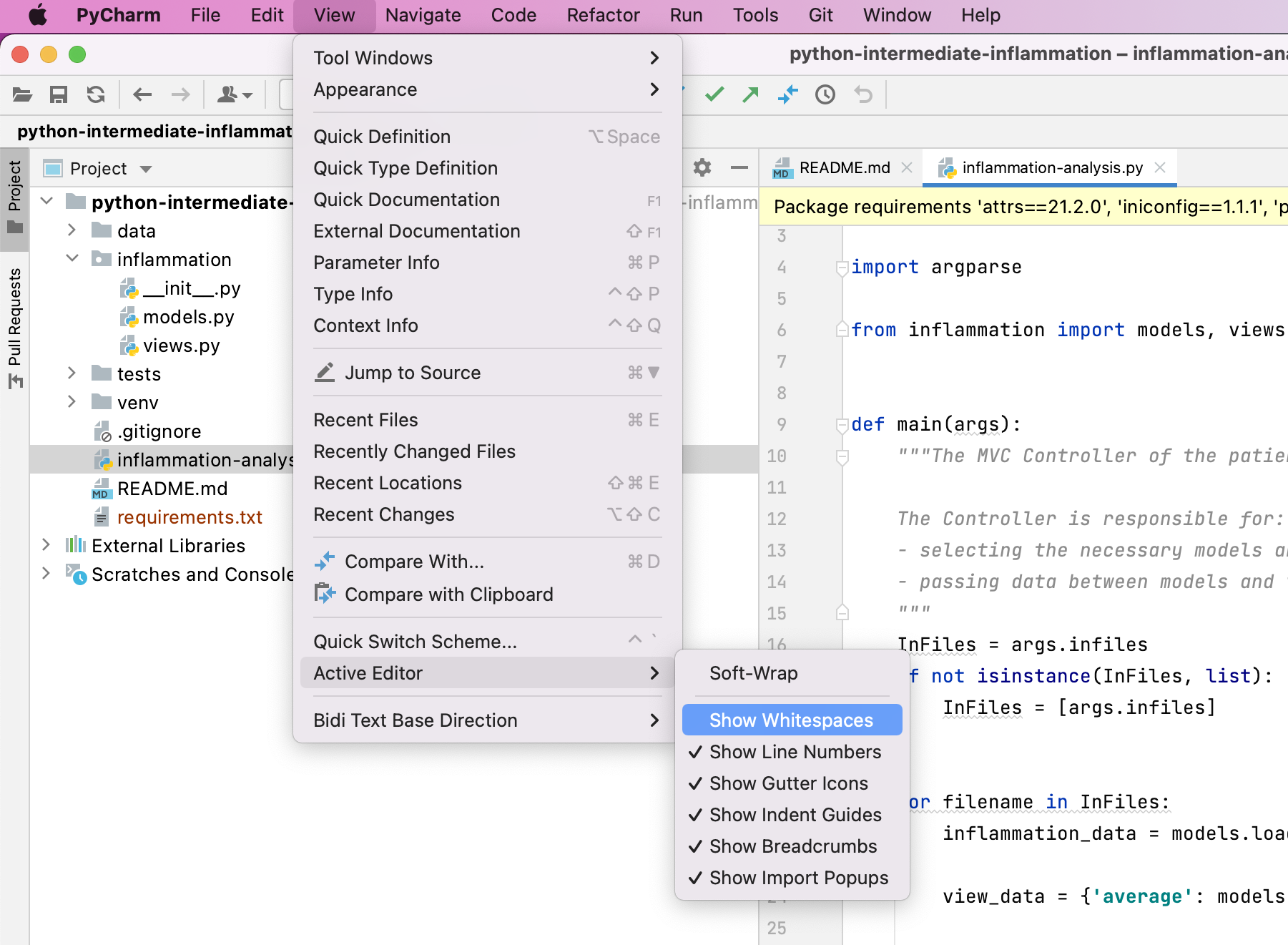

You can also tell the editor to show non-printable characters if you are ever unsure what character exactly is

being used by selecting View>Active Editor>Show whitespace.

There are more complex rules on indenting single units of code that continue over several lines, e.g. function,

list or dictionary definitions can all take more than one line. The preferred way of wrapping such long lines is by

using Python’s implied line continuation inside delimiters such as parentheses (()), brackets ([]) and braces

({}), or a hanging indent.

# Add an extra level of indentation (extra 4 spaces) to distinguish arguments from the rest of the code that follows

def long_function_name(

var_one, var_two, var_three,

var_four):

print(var_one)

# Aligned with opening delimiter

foo = long_function_name(var_one, var_two,

var_three, var_four)

# Use hanging indents to add an indentation level like paragraphs of text where all the lines in a paragraph are

# indented except the first one

foo = long_function_name(

var_one, var_two,

var_three, var_four)

# Using hanging indent again, but closing bracket aligned with the first non-blank character of the previous line

a_long_list = [

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]], [[0.33, 0.66, 1], [0.66, 0.83, 1], [0.77, 0.88, 1]]

]

# Using hanging indent again, but closing bracket aligned with the start of the multiline contruct

a_long_list2 = [

1,

2,

3,

# ...

79

]

More details on good and bad practices for continuation lines can be found in PEP 8 guideline on indentation.

Maximum Line Length

All lines should be up to 80 characters long; for lines containing comments or docstrings (to be covered later) the

line length limit should be 73 - see this discussion for reasoning behind these numbers. Some teams strongly prefer a longer line length, and seemed to have settled on the

length of 100. Long lines of code can be broken over multiple lines by wrapping expressions in delimiters, as

mentioned above (preferred method), or using a backslash (\) at the end of the line to indicate

line continuation (slightly less preferred method).

# Using delimiters ( ) to wrap a multi-line expression

if (a == True and

b == False):

# Using a backslash (\) for line continuation

if a == True and \

b == False:

Should a Line Break Before or After a Binary Operator?

Lines should break before binary operators so that the operators do not get scattered across different columns on the screen. In the example below, the eye does not have to do the extra work to tell which items are added and which are subtracted:

# PEP 8 compliant - easy to match operators with operands

income = (gross_wages

+ taxable_interest

+ (dividends - qualified_dividends)

- ira_deduction

- student_loan_interest)

Blank Lines

Top-level function and class definitions should be surrounded with two blank lines. Method definitions inside a class should be surrounded by a single blank line. You can use blank lines in functions, sparingly, to indicate logical sections.

Whitespace in Expressions and Statements

Avoid extraneous whitespace in the following situations:

- immediately inside parentheses, brackets or braces

# PEP 8 compliant: my_function(colour[1], {id: 2}) # Not PEP 8 compliant: my_function( colour[ 1 ], { id: 2 } ) - Immediately before a comma, semicolon, or colon (unless doing slicing where the colon acts like a binary operator

in which case it should should have equal amounts of whitespace on either side)

# PEP 8 compliant: if x == 4: print(x, y); x, y = y, x # Not PEP 8 compliant: if x == 4 : print(x , y); x , y = y, x - Immediately before the open parenthesis that starts the argument list of a function call

# PEP 8 compliant: my_function(1) # Not PEP 8 compliant: my_function (1) - Immediately before the open parenthesis that starts an indexing or slicing

# PEP 8 compliant: my_dct['key'] = my_lst[id] first_char = my_str[:, 1] # Not PEP 8 compliant: my_dct ['key'] = my_lst [id] first_char = my_str [:, 1] - More than one space around an assignment (or other) operator to align it with another

# PEP 8 compliant: x = 1 y = 2 student_loan_interest = 3 # Not PEP 8 compliant: x = 1 y = 2 student_loan_interest = 3 - Avoid trailing whitespace anywhere - it is not necessary and can cause errors. For example, if you use

backslash (

\) for continuation lines and have a space after it, the continuation line will not be interpreted correctly. - Surround these binary operators with a single space on either side: assignment (=), augmented assignment (+=, -= etc.), comparisons (==, <, >, !=, <>, <=, >=, in, not in, is, is not), booleans (and, or, not).

- Don’t use spaces around the = sign when used to indicate a keyword argument assignment or to indicate a

default value for an unannotated function parameter

# PEP 8 compliant use of spaces around = for variable assignment axis = 'x' angle = 90 size = 450 name = 'my_graph' # PEP 8 compliant use of no spaces around = for keyword argument assignment in a function call my_function( 1, 2, axis=axis, angle=angle, size=size, name=name)

String Quotes

In Python, single-quoted strings and double-quoted strings are the same. PEP8 does not make a recommendation for this apart from picking one rule and consistently sticking to it. When a string contains single or double quote characters, use the other one to avoid backslashes in the string as it improves readability.

Naming Conventions

There are a lot of different naming styles in use, including:

- b (single lowercase letter)

- B (single uppercase letter)

- lowercase

- lower_case_with_underscores

- UPPERCASE

- UPPER_CASE_WITH_UNDERSCORES

- CapitalisedWords (or PascalCase) (note: when using acronyms in CapitalisedWords, capitalise all the letters of the acronym, e.g HTTPServerError)

- camelCase (differs from CapitalisedWords/PascalCase by the initial lowercase character)

- Capitalised_Words_With_Underscores

As with other style guide recommendations - consistency is key. Pick one and stick to it, or follow the one already established if joining a project mid-way. Some things to be wary of when naming things in the code:

- Avoid using the characters ‘l’ (lowercase letter L), ‘O’ (uppercase letter o), or ‘I’ (uppercase letter i) as single character variable names. In some fonts, these characters are indistinguishable from the numerals one and zero. When tempted to use ‘l’, use ‘L’ instead.

- Avoid using non-ASCII (e.g. UNICODE) characters for identifiers

- If your audience is international and English is the common language, try to use English words for identifiers and comments whenever possible but try to avoid abbreviations/local slang as they may not be understood by everyone. Also consider sticking with either ‘American’ or ‘British’ English spellings and try not to mix the two.

Function, Variable, Class, Module, Package Naming

- Function and variable names should be lowercase, with words separated by underscores as necessary to improve readability.

- Class names should normally use the CapitalisedWords convention.

- Modules should have short, all-lowercase names. Underscores can be used in the module name if it improves readability.

- Packages should also have short, all-lowercase names, although the use of underscores is discouraged.

A more detailed guide on naming functions, modules, classes and variables is available from PEP8.

Comments

Comments allow us to provide the reader with additional information on what the code does - reading and understanding source code is slow, laborious and can lead to misinterpretation, plus it is always a good idea to keep others in mind when writing code. A good rule of thumb is to assume that someone will always read your code at a later date, and this includes a future version of yourself. It can be easy to forget why you did something a particular way in six months’ time. Write comments as complete sentences and in English unless you are 100% sure the code will never be read by people who don’t speak your language.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Comments

As a side reading, check out the ‘Putting comments in code: the good, the bad, and the ugly’ blogpost. Remember - a comment should answer the ‘why’ question”. Occasionally the “what” question. The “how” question should be answered by the code itself.

Block comments generally apply to some (or all) code that follows them, and are indented to the same level as that

code. Each line of a block comment starts with a # and a single space (unless it is indented text inside the comment).

def fahr_to_cels(fahr):

# Block comment example: convert temperature in Fahrenheit to Celsius

cels = (fahr + 32) * (5 / 9)

return cels

An inline comment is a comment on the same line as a statement. Inline comments should be separated by at least two

spaces from the statement. They should start with a # and a single space and should be used sparingly.

def fahr_to_cels(fahr):

cels = (fahr + 32) * (5 / 9) # Inline comment example: convert temperature in Fahrenheit to Celsius

return cels

Python doesn’t have any multi-line comments, like you may have seen in other languages like C++ or Java. However, there are ways to do it using docstrings as we’ll see in a moment.

The reader should be able to understand a single function or method from its code and its comments, and should not have to look elsewhere in the code for clarification. The kind of things that need to be commented are:

- Why certain design or implementation decisions were adopted, especially in cases where the decision may seem counter-intuitive

- The names of any algorithms or design patterns that have been implemented

- The expected format of input files or database schemas

However, there are some restrictions. Comments that simply restate what the code does are redundant, and comments must be accurate and updated with the code, because an incorrect comment causes more confusion than no comment at all.

Exercise: Improve Code Style of Our Project

Let’s look at improving the coding style of our project. First create a new feature branch called

style-fixesoff ourdevelopbranch and switch to it (from the project root):$ git checkout develop $ git checkout -b style-fixesNext look at the

inflammation-analysis.pyfile in PyCharm and identify where the above guidelines have not been followed. Fix the discovered inconsistencies and commit them to the feature branch.Solution

Modify

inflammation-analysis.pyfrom PyCharm, which is helpfully marking inconsistencies with coding guidelines by underlying them. There are a few things to fix ininflammation-analysis.py, for example:

Line 24 in

inflammation-analysis.pyis too long and not very readable. A better style would be to use multiple lines and hanging indent, with the closing brace `}’ aligned either with the first non-whitespace character of the last line of list or the first character of the line that starts the multiline construct or simply moved to the end of the previous line. All three acceptable modifications are shown below.# Using hanging indent, with the closing '}' aligned with the first non-blank character of the previous line view_data = { 'average': models.daily_mean(inflammation_data), 'max': models.daily_max(inflammation_data), 'min': models.daily_min(inflammation_data) }# Using hanging indent with the, closing '}' aligned with the start of the multiline contruct view_data = { 'average': models.daily_mean(inflammation_data), 'max': models.daily_max(inflammation_data), 'min': models.daily_min(inflammation_data) }# Using hanging indent where all the lines of the multiline contruct are indented except the first one view_data = { 'average': models.daily_mean(inflammation_data), 'max': models.daily_max(inflammation_data), 'min': models.daily_min(inflammation_data)}Variable ‘InFiles’ in

inflammation-analysis.pyuses CapitalisedWords naming convention which is recommended for class names but not variable names. By convention, variable names should be in lowercase with optional underscores so you should rename the variable ‘InFiles’ to, e.g., ‘infiles’ or ‘in_files’.There is an extra blank line on line 20 in

inflammation-analysis.py. Normally, you should not use blank lines in the middle of the code unless you want to separate logical units - in which case only one blank line is used. Note how PyCharm is warning us by underlying the whole line.Only one blank line after the end of definition of function

mainand the rest of the code on line 30 ininflammation-analysis.py- should be two blank lines. Note how PyCharm is warning us by underlying the whole line.Finally, let’s add and commit our changes to the feature branch. We will check the status of our working directory first.

$ git statusOn branch style-fixes Changes not staged for commit: (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed) (use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory) modified: inflammation-analysis.py no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Git tells us we are on branch

style-fixesand that we have unstaged and uncommited changes toinflammation-analysis.py. Let’s commit them to the local repository.$ git add inflammation-analysis.py $ git commit -m "Code style fixes."

Optional Exercise: Improve Code Style of Your Other Python Projects

If you have another Python project, check to which extent it conforms to PEP8 coding style.

Documentation Strings aka Docstrings

If the first thing in a function is a string that is not assigned to a variable, that string is attached to the function as its documentation. Consider the following code implementing function for calculating the nth Fibonacci number:

def fibonacci(n):

"""Calculate the nth Fibonacci number.

A recursive implementation of Fibonacci array elements.

:param n: integer

:raises ValueError: raised if n is less than zero

:returns: Fibonacci number

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError('Fibonacci is not defined for N < 0')

if n == 0:

return 0

if n == 1:

return 1

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2)

Note here we are explicitly documenting our input variables, what is returned by the function, and also when the

ValueError exception is raised. Along with a helpful description of what the function does, this information can

act as a contract for readers to understand what to expect in terms of behaviour when using the function,

as well as how to use it.

A special comment string like this is called a docstring. We do not need to use triple quotes when writing one, but

if we do, we can break the text across multiple lines. Docstrings can also be used at the start of a Python module (a file

containing a number of Python functions) or at the start of a Python class (containing a number of methods) to list

their contents as a reference. You should not confuse docstrings with comments though - docstrings are context-dependent and should only

be used in specific locations (e.g. at the top of a module and immediately after class and def keywords as mentioned).

Using triple quoted strings in locations where they will not be interpreted as docstrings or

using triple quotes as a way to ‘quickly’ comment out an entire block of code is considered bad practice.

In our example case, we used

the Sphynx/ReadTheDocs docstring style formatting

for the param, raises and returns - other docstring formats exist as well.

Python PEP 257 - Recommendations for Docstrings

PEP 257 is another one of Python Enhancement Proposals and this one deals with docstring conventions to standardise how they are used. For example, on the subject of module-level docstrings, PEP 257 says:

The docstring for a module should generally list the classes, exceptions and functions (and any other objects) that are exported by the module, with a one-line summary of each. (These summaries generally give less detail than the summary line in the object's docstring.) The docstring for a package (i.e., the docstring of the package's `__init__.py` module) should also list the modules and subpackages exported by the package.Note that

__init__.pyfile used to be a required part of a package (pre Python 3.3) where a package was typically implemented as a directory containing an__init__.pyfile which got implicitly executed when a package was imported.

So, at the beginning of a module file we can just add a docstring explaining the nature of a module. For example, if

fibonacci() was included in a module with other functions, our module could have at the start of it:

"""A module for generating numerical sequences of numbers that occur in nature.

Functions:

fibonacci - returns the Fibonacci number for a given integer

golden_ratio - returns the golden ratio number to a given Fibonacci iteration

...

"""

...

The docstring for a function or a module is returned when

calling the help function and passing its name - for example from the interactive Python console/terminal available

from the command line or when rendering code documentation online

(e.g. see Python documentation).

PyCharm also displays the docstring for a function/module in a little help popup window when using tab-completion.

help(fibonacci)

Exercise: Fix the Docstrings

Look into

models.pyin PyCharm and improve docstrings for functionsdaily_mean,daily_min,daily_max. Commit those changes to feature branchstyle-fixes.Solution

For example, the improved docstrings for the above functions would contain explanations for parameters and return values.

def daily_mean(data): """Calculate the daily mean of a 2D inflammation data array for each day. :param data: A 2D data array with inflammation data (each row contains measurements for a single patient across all days). :returns: An array of mean values of measurements for each day. """ return np.mean(data, axis=0)def daily_max(data): """Calculate the daily maximum of a 2D inflammation data array for each day. :param data: A 2D data array with inflammation data (each row contains measurements for a single patient across all days). :returns: An array of max values of measurements for each day. """ return np.max(data, axis=0)def daily_min(data): """Calculate the daily minimum of a 2D inflammation data array for each day. :param data: A 2D data array with inflammation data (each row contains measurements for a single patient across all days). :returns: An array of minimum values of measurements for each day. """ return np.min(data, axis=0)Once we are happy with modifications, as usual before staging and commit our changes, we check the status of our working directory:

$ git statusOn branch style-fixes Changes not staged for commit: (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed) (use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory) modified: inflammation/models.py no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")As expected, Git tells us we are on branch

style-fixesand that we have unstaged and uncommited changes toinflammation/models.py. Let’s commit them to the local repository.$ git add inflammation/models.py $ git commit -m "Docstring improvements."

In the previous exercises, we made some code improvements on feature branch style-fixes. We have committed our

changes locally but have not pushed this branch remotely for others to have a look at our code before we merge it

onto the develop branch. Let’s do that now, namely:

- push

style-fixesto GitHub - merge

style-fixesintodevelop(once we are happy with the changes) - push updates to

developbranch to GitHub (to keep it up to date with the latest developments) - finally, merge

developbranch into the stablemainbranch

Here is a set commands that will achieve the above set of actions (remember to use git status often in between other

Git commands to double check which branch you are on and its status):

$ git push -u origin style-fixes

$ git checkout develop

$ git merge style-fixes

$ git push origin develop

$ git checkout main

$ git merge develop

$ git push origin main

Typical Code Development Cycle

What you’ve done in the exercises in this episode mimics a typical software development workflow - you work locally on code on a feature branch, test it to make sure it works correctly and as expected, then record your changes using version control and share your work with others via a centrally backed-up repository. Other team members work on their feature branches in parallel and similarly share their work with colleagues for discussions. Different feature branches from around the team get merged onto the development branch, often in small and quick development cycles. After further testing and verifying that no code has been broken by the new features - the development branch gets merged onto the stable main branch, where new features finally resurface to end-users in bigger “software release” cycles.

Key Points

Always assume that someone else will read your code at a later date, including yourself.

Community coding conventions help you create more readable software projects that are easier to contribute to.

Python Enhancement Proposals (or PEPs) describe a recommended convention or specification for how to do something in Python.

Style checking to ensure code conforms to coding conventions is often part of IDEs.

Consistency with the style guide is important - whichever style you choose.