|

|

Version 1.0

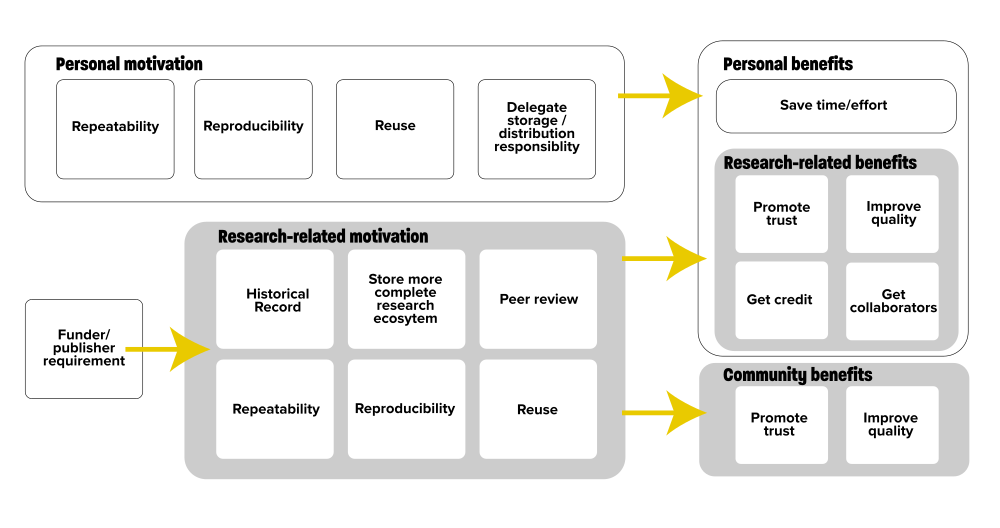

Research software can be any collection of scripts or code written for, or used within, a research context. For example, a 50 line bash shell script for manipulating and filtering files, a collection of 50 line R scripts for running a bioinformatics analysis, 10,000 lines of Java for medical image analysis or 100,000 lines of Fortran using MPI for computational fluid dynamics are all examples of research software. But, why bother depositing research software into a digital repository? Why go to all that time and effort? What are the benefits to researchers for doing so? This guide describes some of the significant benefits that depositing research software delivers, both to you and to the research community. and also addresses concerns that you may have about sharing your software with others.

Why deposit software

This guide is one of a series of guides on software deposit, written by The Software Sustainability Institute 1, funded by Jisc 2. For an overview of the series, see Michael Jackson (ed.) (07 August 2018). Software Deposit: Guidance for Researchers (Version 1.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1327310. Online: https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance/SoftwareDepositGuidance.html.

By depositing your software within a digital repository, the exact versions of your software upon which you have published your research results is retained and remains available for future use both by yourself and by other researchers. You enable other researchers, and your future self, to inspect, replicate, reproduce and reuse your research, as manifested in your software, in the short term and to inspect, for the historical record, in the long term. It allows your software to remain available beyond the lifetime of your current project, or your current employment at a specific institution.

Even if, in the long term, it is no longer possible to compile or run your software's source code, it still serves as a valuable historical record, as a programmatic description of how your research was implemented.

Taken together, research software, data, facilities, equipment and an overarching research question can be viewed as a research activity or experiment, worthy to be published. Conversely, a publication can be considered as a narrative that describes how the research objects are used together to reply to the research question.

By depositing not just papers, but software and data sets 3 as well, you are storing a more complete record of this ecosystem for future use of both yourself and others. Furthermore, many digital repositories allow you to explicitly express these relationships between your research outputs.

The results published in a paper are not typically produced by the method described in the paper. More commonly, they are produced by the implementation of that method using the other research outputs in the ecosystem, which includes the software. Your method may be scientifically valid, but your implementation may be flawed, which may give you misleading results, from which you draw incorrect conclusions. Making your software available can allow others to validate what you have done and to determine whether your conclusions are valid.

Continuing on from the above, allowing others to validate what you have done can promote trust in your research, that you have nothing to hide and are open to others inspecting what you have done. Yes, it is possible that errors will be found, but having mistakes identified offers a learning experience and an opportunity to improve the quality of your code for the next time. More importantly, it allows scientific outcomes, derived from data produced by the software, to be corrected and conclusions re-evaluated in light of these

Events such as the "ClimateGate" controversy of 2009 4 provide a worst-case example of what can happen when poor quality research software is developed away from the critical eyes of the community.

When you deposit your software into a digital repository you can get a unique persistent digital identifier for your deposit (for example, a DOI 5 or an ARK 6). Others can cite this identifier to identify the exact version of your software that they used in their research, rather than just citing, for example, just your software's name and a URL (which may break in future), or a related paper (which, as mentioned above, is not your software itself).

In the same way you can expect others to cite your papers if they use them within their research, or to cite data 7 of yours that you have deposited and they have used, you can request that others cite your software and so get attribution when your research, as manifested in your software, is used by others.

You can search for these citations in papers, publications, documentation, web pages, blog posts and other software and so gather information relating to impact of your software. This can help you to demonstrate the impact of your software and its contribution to research to your employers, your fellow researchers and your funders. It allows you and your fellow authors, including non-academic researchers who may have developed the software with you, to get recognition and credit for this valuable research output. Some digital repositories provide features to track citations and count downloads 8 to help you gather this information.

Researchers who read about your research, via a paper, for example, and then are able to reproduce or reuse your research, via using your research software, can be viewed as possible collaborators for future projects.

Other researchers reading your publications may contact you for your software, after reading a related paper or seeing a presentation at a conference. Directing them to a digital repository with your software is far quicker than having to rake through your files, find the version of the software they need, bundle this up and send it to them.

More generally, having a digital repository manage hosting of your deposit is less time consuming than having to manage this yourself, on a departmental web server for example.

Your funder or a publisher may require, or recommend, that you deposit your software into a digital repository. Your funder may want to ensure that the research that they have funded remains available. A publisher may want your software to be provided as a complement to any papers you publish which describe results which were, in some way, produced using your software.

Funders and publishers may support the concept of open access 9, by which research outputs, including software, are distributed online and free of cost. For example, Wellcome Open Research require that software written by a paper's authors be deposited and recommend the use of Zenodo for archived software 10, so its title, DOI and licence can be cited. Springer Nature's BioMed Central 11 series of journals, requires both a link to a live version of the software (e.g. on GitHub) but also to an archived version with a DOI, for which Zenodo is recommended 12.

You may be concerned that you deposit your software then other researchers use your software to generate results and publish these before you yourself have a chance to.

There is a distinction between the time at which software is deposited into a digital repository and the time when it is published so that others can view it. Many digital repositories, including Zenodo 13 and figshare 14, support embargoes which allow you to specify a date when you want the deposit to be made publicly available. So, for example, you could choose to set an embargo on your software deposit so that it is only made public after any related papers have been published.

A deposit can be embargoed for a long time. For example, the University of Edinburgh DataShare supports embargoes of up to 5 years 15.

Another advantage of embargoes is that you can prepare your deposit and describe it, via metadata, while the knowledge of the version of your software being deposited is fresh in your mind.

Software licencing is another means by which you can control how and what other researchers can, and cannot, do with your software. You can, for example, make your software available solely for the purposes of validating your results.

Again, software licencing allows you to control what other researchers can, and cannot, do with your software.

If your software is good enough for you to publish a paper with results based upon its use then it is good enough to be published so that other researchers can, at least, inspect it to validate your methodology. If others express concerns about its state then look upon that as a good thing both in that they are interested in your research and that you can learn from their comments and make improvements in the readability of code you write in future. See the section on "Improve both quality and trust" above.

Related Software deposit guides:

Articles and blog posts on why researchers should share and deposit research software:

Please cite as: Michael Jackson (ed.) (07 August 2018). Software Deposit: Why deposit software (Version 1.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1327333. Online: https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance/WhyDepositSoftware.html.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Software Sustainability Institute, https://www.software.ac.uk.↩

Jisc, https://www.jisc.ac.uk.↩

DCC (2014). "Five steps to decide what data to keep: a checklist for appraising research data v.1". Edinburgh: Digital Curation Centre. Available online: http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/how-guides/five-steps-decide-what-data-keep.↩

Climatic Research Unit email controversy, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climatic_Research_Unit_email_controversy.↩

Digital Object Identifier (DOI), https://www.doi.org/.↩

Archival Resource Key (ARK) J. Kunze and R. Rogers (2008) The ARK Identifier Scheme, California Digital Library and US National Library of Medicine, May 2008. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p9863nc.↩

Ball, A. & Duke, M. (2015). 'How to Cite Datasets and Link to Publications'. DCC How-to Guides. Edinburgh: Digital Curation Centre. Available online: http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/how-guides.↩

See, for example, figshare, https://figshare.com/, or the University of Edinburgh DataShare, https://datashare.is.ed.ac.uk, which logs views by deposit page and deposited file.↩

Open access, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_access.↩

"Software & source code", Wellcome Open Research, https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/for-authors/data-guidelines.↩

BioMed Central, https://www.biomedcentral.com.↩

"Software and code", BioMed Central, https://www.biomedcentral.com/getpublished/editorial-policies.↩

Zenodo, https://zenodo.org.↩

figshare, https://figshare.com.↩

"Checklist for deposit", The University of Edinburgh, https://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/research-support/research-data-service/sharing-preserving-data/data-repository/checklist.↩