|

|

Version 1.0

Research software is an integral part of the modern research ecosystem. Taken together, research software, alongside data, facilities, equipment and an overarching research question can be viewed as a research activity or experiment, worthy to be published. Conversely, a publication can be considered as a narrative that describes how the research objects are used together to reply to the research question.

Depositing research software into a digital repository can offer significant benefits. By depositing not just papers, but software, and data sets, as well, researchers can store a more complete record of this ecosystem for future use to both the researchers who undertook the research and also the wider research community. Making research software available allows other researchers to inspect, replicate, reproduce and reuse the research, as manifested in the software, in the short term and to inspect, for the historical record, in the long term. It allows research software to remain available beyond the lifetime of any current project, or a researcher's current employment at a specific institution. Digital repositories can also provide unique persistent digital identifiers for software which can be cited and help researchers to get attribution and credit for their research software when it is used by others.

The Software Sustainability Institute 1, funded by Jisc 2 have developed a set of complementary guides covering the main aspects of depositing software into digital repositories. These guides are intended for researchers, principal investigators and research leaders and research data and digital repository managers. This document provides an overview of the content covered by the guides.

The Software Sustainability Institute takes the view that research software is any software used in research and does not differentiate between what are often termed scripts, written in scripting languages such as bash shell or Python or R, and programs, written in "traditional" programming languages such as C, C++, Fortran or Java. In the view of the Institute a 50 line bash shell script for manipulating and filtering files, a collection of 50 line R scripts for running a bioinformatics analysis, 10,000 lines of Java for medical image analysis or 100,000 lines of Fortran using MPI for computational fluid dynamics are all examples of research software and may be suitable candidates for deposit into a digital repository. It is this view of research software that is assumed throughout the guides.

The guiding principles that motivated the form and content of the guides were as follows.

Mandate little, recommend lots, focus not on "best practice" but "good enough, or better than at present, practice". This was motivated by Beals et al. (2018) in particular the observation that "Incremental progress is still progress."

Emphasise the importance of deposits to allow others to inspect, replicate, reproduce and reuse in the short term and inspect, for the historical record, in the long term. This was motivated by Brown (2017)'s argument that "[I]t is at least plausible to argue that we don't really care about our ability to exactly re-run a decade old computational analysis. What we do care about is our ability to figure out what was run and what the important decisions were - something that Yolanda Gil refers to as 'inspectability.' ... exact repeatability has a short shelf-life.".

Take no position on whether or not to deposit binaries, containers or virtual machines. Whether these provide solutions to issues around replicability, reproducibility and reuse of research software or spawn a different set of problems is very much an open question (compare, for example, Haines and Jay (2016) versus Brown (2017)). The guides do not mandate or suggest depositing such artefacts but nor do they preclude them.

Provide lists of key points or things to do, only a few pages long, with minimal rationale. Direct researchers to other resources for further information. This was motivated by a recommendation in Brown et al. (2018) that guidance "for stakeholders e.g. researchers, research data managers, institutions and publishers, needs to speak their respective languages, not require significant time or effort to apply and be free of developer jargon."

Consider deposits of software as attachments or ancillary files submitted alongside publications to publishers to be out-of-scope. Instead, software is considered as a first class research object, worthy of deposit as an object in its own right. However, much of the guidance in these guides (especially what to deposit and how to describe such deposits) would apply to depositing software in this scenario too.

The guides and their target audiences are shown in the following table. Each guide, plus this overview document, has been published via Zenodo 3 and the DOIs are shown below. The guides are also available online 4 and this online resource will also, in time, host resources that complement the guides including links to examples of what are considered to be good software deposits and good research software generally supported with commentary on why these are considered to be good.

| Guide | Researchers | Principal Investigators | Research Data Managers | DOI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Why deposit software | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327333 | ||

| When to deposit software | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327331 | ||

| Where to deposit software | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327329 | ||

| How to deposit software | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327327 | |||

| What to deposit | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327325 | ||

| What not to deposit | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327323 | ||

| How to describe a software deposit | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327321 | ||

| How to choose a software licence | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327316 | ||

| How to review a software deposit | ✔ | ✔ | 10.5281/zenodo.1327314 |

A summary of the content of each guide now follows.

Why deposit software

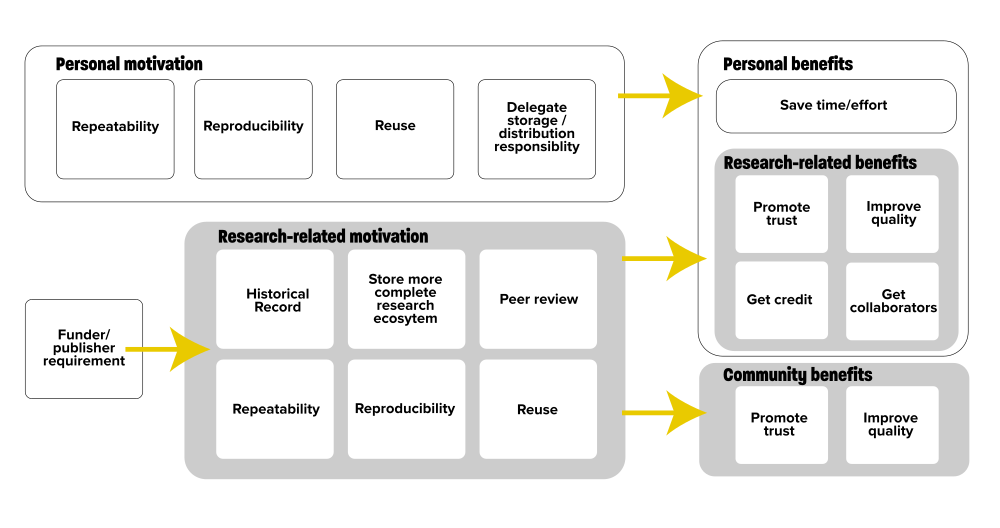

Why bother depositing research software into a digital repository? Why go to all that time and effort? What are the benefits to researchers for doing so? "Why deposit software" describes some of the significant benefits that depositing research software delivers, both to individual researchers and to the research community and also addresses concerns that they may have about sharing their software with others.

When to deposit software

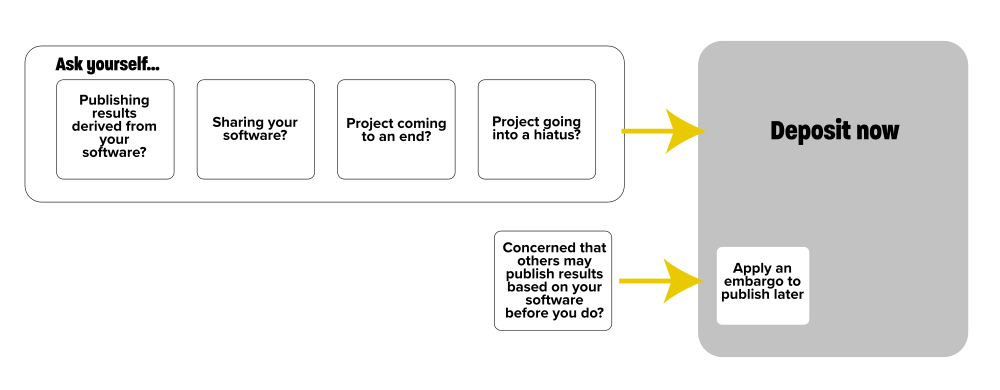

A researcher may be convinced of the importance and benefits of depositing research software within a digital repository, so that the exact versions of their software upon which they have published their research results are retained and remain available for future inspection and use, both by themselves and by other researchers. But, the researcher may ask, when is the best time for them to deposit their software? "When to deposit software" poses a series of questions for researchers to ask themselves. If the answer to any of these questions is "yes", then that is the time for them to deposit their software.

Where to deposit software

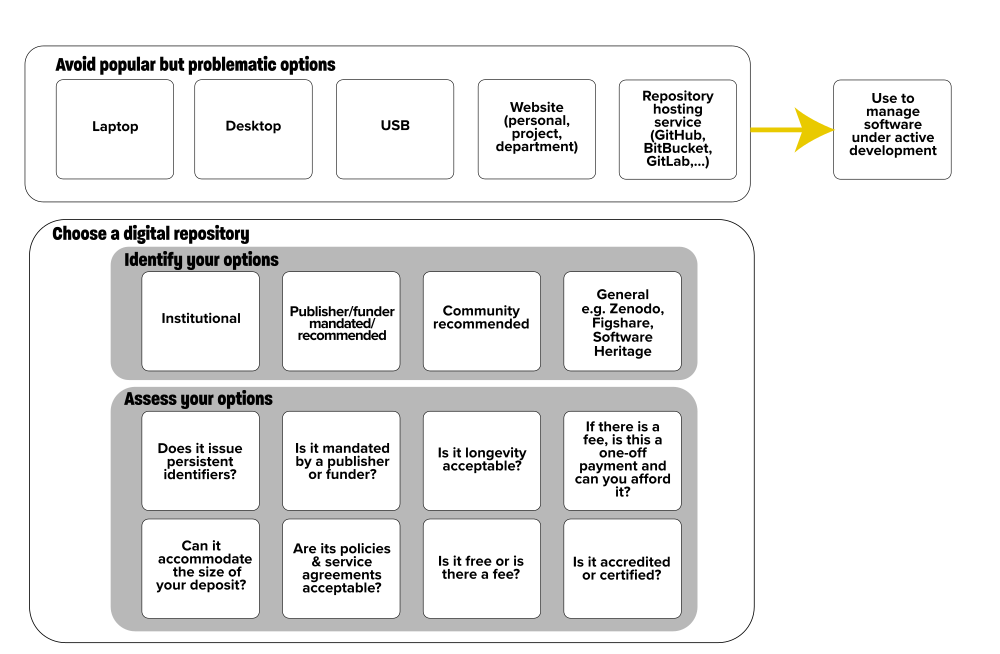

There are myriad digital repositories where researchers can deposit their research software so that the exact versions of their software upon which they have published their research results are retained and remain available for future inspection and use, both by themselves and by other researchers. These digital repositories may be provided by their institutions, recommended, or mandated, by funders or publishers, or provided as a service to research communities by third-party organisations. "Where to deposit software" provides advice to researchers on choosing where to deposit their software.

How to deposit software

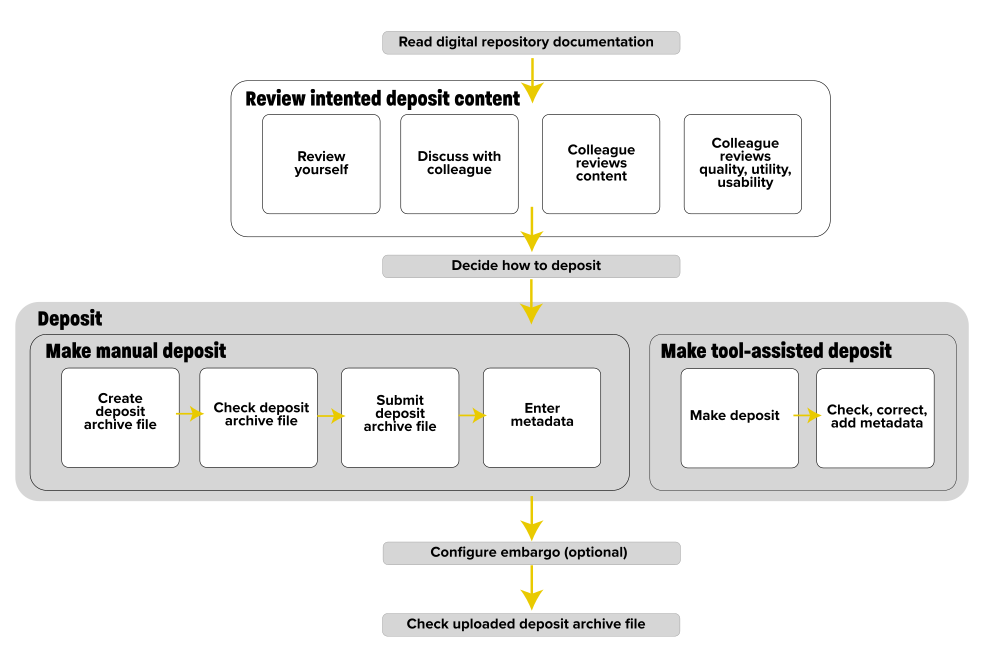

Different digital repositories have different means of submission and different requirements as to the deposits they will accept, the metadata associated with these deposits and how deposits are done. However, regardless of the digital repository that a researcher will use, there are some common tasks that a researcher should do before, during and after they deposit their software. "How to deposit software" describes these tasks.

What to deposit

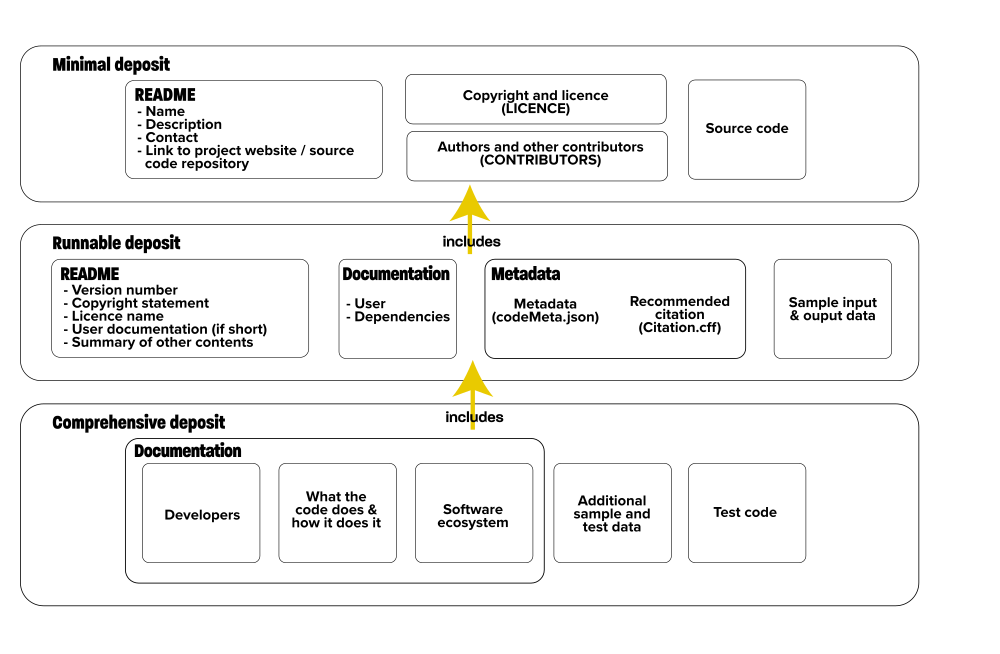

What do we mean by a "software deposit"? What does a software deposit need to contain to enable it to allow other researchers to inspect, replicate, reproduce and reuse the research, as manifested in the software, in the short term and inspect the software, for the historical record, in the long term. "What to deposit" describes what a software deposit should include, in terms of three types of deposit: a minimal deposit (with a README, source code, copyright, licence and contributors information), a runnable deposit (with additional user documentation and sample data) and a comprehensive deposit (providing a rich set of code, data and documentation relating to the software).

What not to deposit

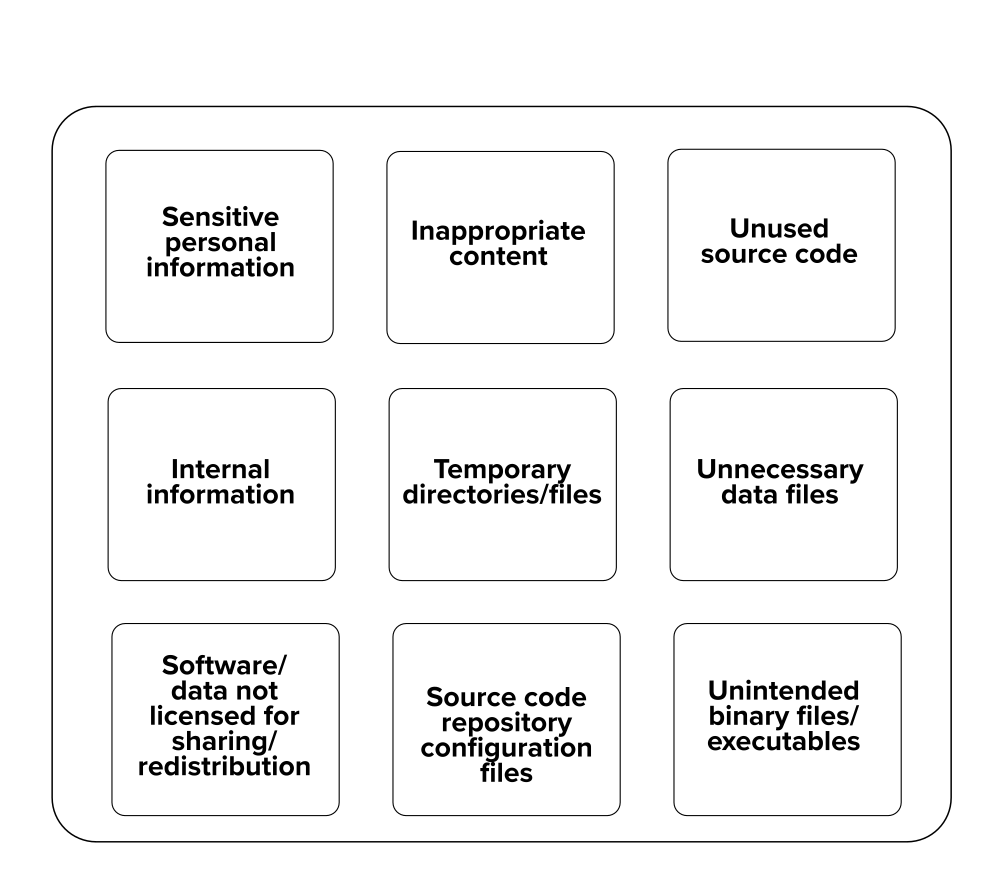

A software deposit lodged within a digital repository can contain myriad content. But there is certain content that should not be included within a software deposit. Some of this content may be innocuous and only result in a deposit being more bloated than it otherwise needs to be. Some of this content may compromise a researcher's security. And, in the worst case, some of this content may result in a researcher inadvertently breaking local laws relating to data protection. "What not to deposit" summarises the content should not be deposited with a researcher's software.

How to describe a software deposit

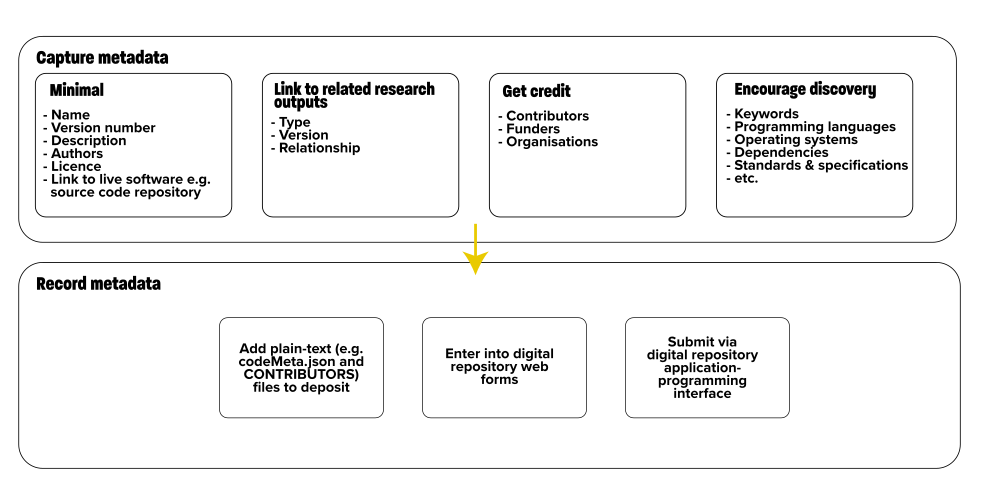

Papers have titles, authors, abstracts, subject categories and keywords, all of which are metadata, data which describes the paper. These metadata help others to categorise and index papers and find papers of interest to them. Metadata can serve a similar purpose for software deposits, providing a description of a software deposit. This metadata can help a researcher get credit for their software, help digital repository managers categorise and index their software deposit and help other researchers find this software according to criteria of relevance to them. Researchers will need this metadata when depositing their software into a digital repository. "How to describe a software deposit" summarises the metadata researchers can, and should, capture.

How to choose a software licence

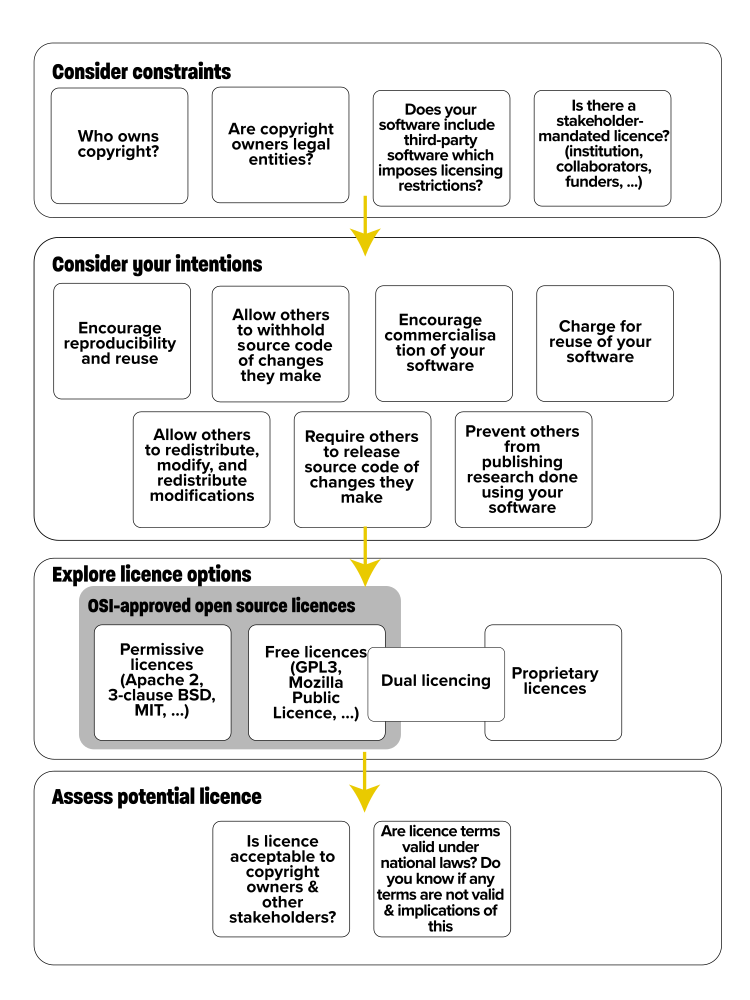

By depositing software into a digital repository, a researcher is implicitly stating that, at some point in time, they expect, or hope, someone will download it, with the aim of inspecting, replicating, reproducing or reusing their research. A software licence is an explicit, and legally-binding, statement of what others can, and cannot, do with a researcher's software and any obligations upon them. "How to choose a software licence" provides an overview of the licensing options available - specifically open source licences, proprietary licences and dual licencing - and the key qualities of each in respect to allowing others to inspect, use and reuse research software.

How to review a software deposit

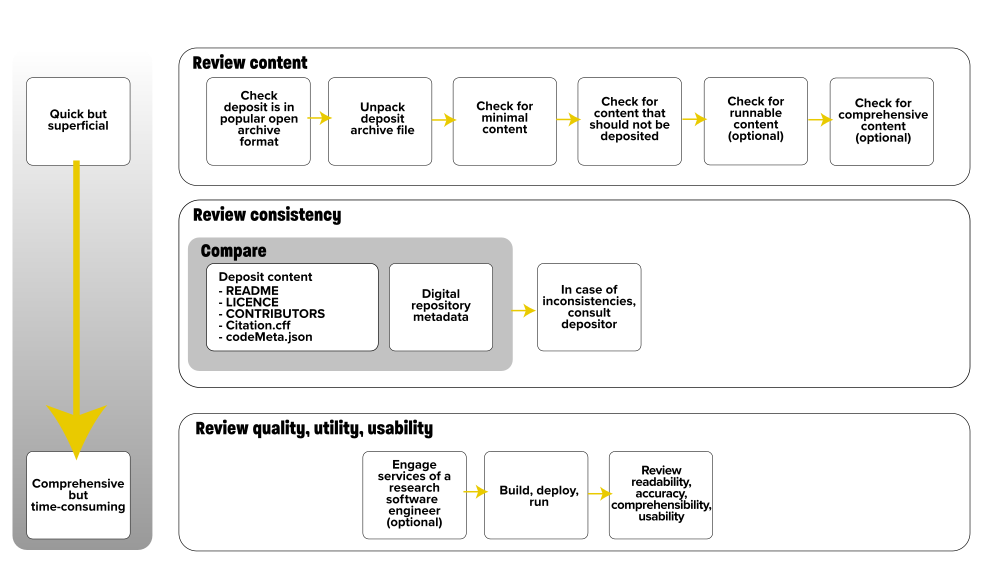

Digital repositories can differ in the deposits that they accept, the metadata requested from researchers, how researchers make their deposits and how these deposits are processed. This includes how deposits are reviewed post-deposit and pre-publication and the criteria that are used in these reviews. Despite the differences between individual digital repositories, there are some common checks that can be done for any software deposit. The nature and degree to which a software deposit can be reviewed depends upon the time, effort and expertise available. "How to review a software deposit" describes three approaches to reviewing a deposit: a quick content review, a more detailed consistency review and a comprehensive review of quality, utility and usability.

The following terms are used throughout the guides.

Digital preservation system: a repository, archive or service that also hosts digital artefacts, including research outputs, but also implements strategies to afford long term access to the digital artefacts, in the face of technological changes. For example, Archivematica 5. Preservica 6 or Arkivum Perpetua 7.

Digital repository: a repository, archive or service that hosts digital artefacts, including research outputs such as papers, presentations, data sets and software. For example, Zenodo 8, figshare 9, DSpace 10 or Samvera 11.

Inspect: read source code, supporting narratives and papers to understand what was run, the environment in which it was run, important decisions that were made, how results were produced and to identify any flaws.

Repeat: the same lab runs the same experiment with the same set up to try and get the same result.

Replicate: an independent lab runs the same experiment with the same set up.

Reproduce: an independent lab varies the experiment or set up to try and get similar results.

Repository hosting service: a service that hosts source code repositories within an institution, within a community, or for myriad individuals and communities. For example, GitHub 12, BitBucket 13, GitLab 14, CCPForge 15 or Microsoft Visual Studio Team Services 16.

Rerun: the same or independent labs running the same or different experiments with the same or different set ups.

Research software: any collection of scripts or code written for, or used within, a research context. For example, a 50 line bash shell script for manipulating and filtering files, a collection of 50 line R scripts for running a bioinformatics analysis, 10,000 lines of Java for medical image analysis or 100,000 lines of Fortran using MPI for computational fluid dynamics are all examples of research software and may be suitable candidates for deposit into a digital repository.

Reuse: an independent lab runs a different experiment.

Source code repository: a version control tool, revision control system, source code management tool or source code repository i.e. any tool that manages versions of source code and related files. For example, Git, Mercurial, Subversion or Microsoft Team Foundation Version Control.

The writing of these guides was done as part of a software deposit and preservation project undertaken by The Software Sustainability Institute and funded by Jisc.

Christopher Brown, Jisc and Neil Chue Hong, The Software Sustainability Institute managed this project and offered valuable advice and guidance throughout.

The following people also offered valuable advice and guidance which contributed to both the content and form of these guides: Steffan Adams, Cardiff University; Matthew Addis, Arkivum; Mario Antonioletti, EPCC; Alessia Bardi, ISTI-CNR; David Clipsham, National Archives; Jonathan Cooper, UCL; Antonin Delpeuch, University of Oxford; Roberto Di Cosmo, Software Heritage; Federica Fina, University of St Andrews; Alistair Grant, EPCC; Morane Gruenpeter, Software Heritage; Maria Guerreiro, eLife Sciences Publications Ltd; Matthew Herring, University of York; Catherine Jones, STFC; Steve D. Jones, University of Bergen; Daniel S. Katz, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; Somaya Langley, University of Cambridge; Antonis Lempesis, Athena Research Center; Joanna Leng, University of Leeds; James Long, University of Plymouth; Mary McDerby, University of Manchester; Rachel MacGregor, University of Lancaster; Hrafn Malmquist, University of Edinburgh; Brian Matthews, STFC; Rowland Mosbergen, QUT (Queensland University of Technology); Martin O'Reilly, Turing Institute; Naomi Penfold, eLife; Edward Ransley, University of Plymouth; Fernando Rios, University of Arizona; Ben Samuels, University of Lincoln; Joshua Sendall, Lancaster University; Matthew Siekier, University of Huddersfield; Justin Simpson, Artefactual Systems; Mark Woodbridge, Imperial College; Wei Xing, Crick Institute.

Selina Aragon, The Software Sustainability Institute, formatted the images.

In addition to material referenced in the "Find out more" and footnotes in the individual guides, the material in the guides has been drawn from the following papers, reports, blog posts and presentations.

Aerts, Dr. (PhD) P.J.C. (DANS) (2017): Sustainable Software Sustainability - Workshop report. DANS. https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xfe-rn2w.

Beals, M.H., Jones, C., Palmer, G., Jackson, M., Wilde, H., Hammersley, J., Grose, D., Long, R., Panescu, A-T. and Whitaker, K. (2018) "Sharing reproducible research - minimum requirements and desirable features", The Software Sustainability Institute blog, 22 May 2018, https://www.software.ac.uk/blog/2018-05-22-sharing-reproducible-research-minimum-requirements-and-desirable-features

Brown, C., Chue Hong, N., Jackson, M. (eds) (2018) Software Deposit and Preservation Policy and Planning Workshop Report, 1.1, The Software Sustainability Institute and Jisc, 4 July 2018. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1304912.

Brown, C.T. (2017) "How I learned to stop worrying and love the coming archivability crisis in scientific software", 11 January 2017. http://ivory.idyll.org/blog/2017-pof-software-archivability.html.

Cooper, N. and Hsing, P-Y (eds.) 2017. "A Guide to Reproducible Code in Ecology and Evolution", British Ecological Society, 2017. https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/guide-to-reproducible-code.pdf

Goble, C. (2016) "What is Reproducibility? The R* Brouhaha", Alan Turing Institute Symposium Reproducibility, Sustainability and Preservation, 6-7 April 2016. https://www.slideshare.net/carolegoble/what-is-reproducibility-gobleclean.

Haines, R., Jay. C. (2016) "Reproducible Research: Citing your execution environment using Docker and a DOI", The Software Sustainability Institute blog, 29 March 2016. https://www.software.ac.uk/blog/2016-09-12-reproducible-research-citing-your-execution-environment-using-docker-and-doi

Jackson, M., Crouch, S. and Baxter, R. (2011) "Software Evaluation Guide", The Software Sustainability Institute. https://www.software.ac.uk/resources/guides-everything/software-evaluation-guide

Penfold, N. (2018) "Sustainability in research communication", SSI CW18, March 2018. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.6033749.v2. [slide 19]

Smith, A.M., Katz, D.S., Niemeyer, K.E. (2016) "Software citation principles". FORCE11 Software Citation Working Group, 2016, PeerJ Computer Science 2:e86. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.86. See also https://www.force11.org/software-citation-principles.

The Software Sustainability Institute. (2016). Checklist for a Software Management Plan. v0.1. Available online: https://www.software.ac.uk/software-management-plans. Raw content: https://github.com/softwaresaved/software-management-plans/blob/aa5ea9f88d477f4f0694d3679c3aab50b6dacc18/SMP_Checklist.yaml.

Storer, T. (2017) "Bridging the Chasm: A Survey of Software Engineering Practice in Scientific Programming". ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) Surveys, Volume 50 Issue 4, October 2017, Article No. 47. doi:10.1145/3084225.

University of Edinburgh. "Benefits of deposit", The University of Edinburgh, https://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/research-support/research-data-service/sharing-preserving-data/data-repository/benefits.

Wilson, G., Aruliah, D.A., Brown, C.T., Chue Hong, N.P. and Davis, M. (2014) "Best Practices for Scientific Computing", PLoS Biol 12(1): e1001745, January 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001745.

Please cite as: Michael Jackson (ed.) (07 August 2018). Software Deposit Guidance (Version 1.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1327310. Online: https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance/SoftwareDepositGuidance.html.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Software Sustainability Institute, http://www.software.ac.uk.↩

Jisc, http://www.jisc.ac.uk.↩

Zenodo, https://zenodo.org.↩

Software Deposit Guidance for Researchers, https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance.↩

Archivematica, https://www.archivematica.org/.↩

Preservica, https://preservica.com/.↩

Arkivum Perpetua, https://arkivum.com/perpetua/.↩

Zenodo, https://zenodo.org.↩

figshare, https://figshare.com.↩

DSpace, http://www.dspace.org.↩

Samvera, https://samvera.org.↩

GitHub, https://github.com.↩

BitBucket, https://bitbucket.com.↩

GitLab, https://gitlab.com.↩

CCPForge, https://ccpforge.cse.rl.ac.uk/gf/.↩

Microsoft Visual Studio Team Services, https://www.visualstudio.com/team-services/.↩