|

|

Version 1.0

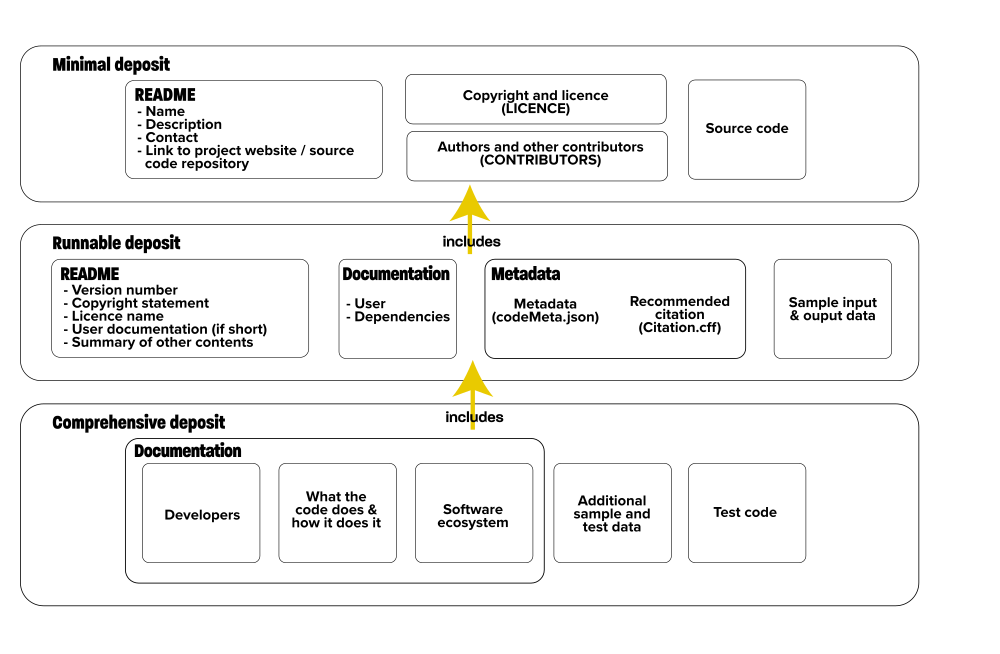

What do we mean by a "software deposit"? What does a software deposit need to contain to enable it to allow other researchers to inspect, replicate, reproduce and reuse the research, as manifested in the software, in the short term and inspect the software, for the historical record, in the long term. This guide describes what a software deposit should include, in terms of three types of deposit: a minimal deposit (with a README, source code, copyright, licence and contributors information), a runnable deposit (with additional user documentation and sample data) and a comprehensive deposit (providing a rich set of code, data and documentation relating to the software).

What to deposit

This guide is one of a series of guides on software deposit, written by The Software Sustainability Institute 1, funded by Jisc 2. For an overview of the series, see Michael Jackson (ed.) (07 August 2018). Software Deposit: Guidance for Researchers (Version 1.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1327310. Online: https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance/SoftwareDepositGuidance.html.

At the very least, a software deposit should have the following content which allows others to access your software and inspect it.

Others will expect to find a plain-text README 3 file in any software bundle. Your deposit should conform to this expectation and provide a README file providing a summary of the key facts about your software. This should include, at the least:

A statement of copyright for your software makes it clear who created, and owns the rights to, your software. A licence makes it clear to others what they can, and cannot, do with your software and any obligations upon them.

Provide your copyright and licence in a plain-text file called LICENCE 5.

If you include third-party components, then include their licences in your LICENCE file, or as separate files in a licences/ directory.

It is important that everyone who authored or otherwise contributed to your software is recognised for doing so and can get credit for their contribution. Provide a plain-text CONTRIBUTORS file which lists people who you deem to have made a significant contribution to your software (including yourself). This can include, for example, columns with each contributor's name, ORCiD identifier and affiliation and brief summary of what their contribution was (for example designer, developer, tester, documentation author etc).

You should also state your funders, providing information on any grants that supported the software's development.

Make sure that any named people have given their consent for their names, ORCiD identifiers and affiliations to be included.

For legacy software, you might want to include statement along the lines of "We have made all efforts to recall contributors. Please get in touch if you contributed to this software and we have forgotten you, so that this can be rectified in future deposits."

Binaries such as executables, Docker 6 or Singularity 7 containers or virtual machine 8 can support replicability and reuse. Depending on the implementation (e.g. how configurable they are) they may also support reproducibility. However, they do not allow others to inspect your software to understand exactly what was run and how your results were produced. A complementary paper may provide this information but the paper does not produce your results, the source code that you run does. Source code has a value even if it no longer can be compiled or run, serving as a programmatic description of the research that was done.

If your source code implements or uses a third-party implementation of algorithms, or analyses that has been published, then ensure that the code has comments with the citations for these publications.

In places where your code uses calls to third-party functions or libraries, it might not be clear to others what these calls are doing, or how you are using them. This can be the case if, for example, a function's purpose is not clear from its name, or it uses default values which you rely upon. Ensure they are commented to make it clear exactly what the function is doing and how it is being used. Complement this with a link to any online documentation for the function.

Ideally, your source code should be well-commented, formatted and indented, to ensure it is easily readable and understandable by others, not just yourself.

A runnable deposit includes everything in a minimal deposit but also includes user documentation, some sample data, includes files to provide a recommended citation and metadata about the deposit. A runnable deposit should allow another researcher to build, install, configure and run your software on the sample data.

Please note that the suggested content for both runnable and comprehensive deposits are just that, suggestions. There is no reason why you can't prepare a deposit that includes some recommended content from a runnable deposit and some from a comprehensive deposit. In our view, the more content, the richer, and more useful, the deposit.

Extend your README by including:

If you want others to run or reuse your software, you need to document how they can do this. You need to provide user documentation. Documentation for users can include: how to build, install, configure and run the software; how to run the software on any sample data sets; and, how to interpret and use the outputs of running your software.

An important part of documentation is your software's dependencies: the environment without which your software cannot be built, installed, configured or run. Even a 10 line script has a dependency on the language used to implement it and the operating systems it runs under. Dependencies should be explicitly documented and not implicitly buried within your source code. It is waste of a someone else's time to build, deploy and run your software only to have it fail an hour later due to a missing library or data set or database.

Documenting your dependencies enable others to understand, and try to get, everything that is needed to run your software and, so help other researchers to replicate, reproduce and reuse your research, as manifested in your software.

Your dependencies can include: operating systems (ones your software run on, others it is known to run on); programming languages; interpreters and compilers; packages, libraries, frameworks, or other tools; browsers; databases; web or other online services and resources; file formats, standards and specifications; data formats, standards and specifications; communications protocols; and, hardware (e.g. 32- or 64-bit platforms, specialised high-performance computing resources, or cloud infrastructures).

For each dependency it can be useful to document the following: name; purpose (i.e. what you use it for); whether it is mandatory or optional; origin (for example, a web site URL, a persistent digital identifier such as a DOI 9 or an ARK 10, the author's email address); copyright and licence; whether it is free or needs payment of a fee; version information (for example, version number, repository commit identifier, date received, date accessed, for an online service, or a persistent digital identifier).

Version information is important. Different versions of dependencies could differ in terms of syntax, behaviour or content. Software written to use one version might not be compatible with earlier or later versions. For example, Python code with the statement "print 'hello'" will not run under Python 3, but code with the statement "print('hello')" will run under both Python 2 and 3.

If you have dependencies that you include in your deposit, for example, if you include copies of source code or data files, then document these too. If you have made any changes, then provide a summary of these. It is a common obligation when redistributing or modifying third-party software that you acknowledge its use, document its inclusion and provide its licence in your deposit.

If you are using a dependency management tool, then some of your dependencies may also be expressed in a programmatic form. For example, a Python pip 11 requirements.txt file; a Maven 12 pom.xml file; a RubyGems 13 Gemfile; an R DESCRIPTION 14 file; an Ansible 15 playbook, or a Vagrant 16 script.

Including sample data can be valuable for those who use your software deposit. These provide users with sample inputs to use with your software and the expected outputs against which they can compare their outputs when running your software. This can help them to determine whether they have managed to build, install and run your software correctly. However, data files can also increase the size of your deposit. The data you provide does not have to be comprehensive, or exercise every feature of your software in every condition, a few sample data sets would suffice.

If you have published, or intend to publish, results based on your data files then consider following the FAIR 17 principles for research data management and deposit them into a digital repository as a citable research object too. You can then use the metadata that describes your software and data deposits to link them together 18.

Changes in dependencies can cause both subtle and not so subtle, changes in outputs for sample input data 19. Document what you consider to be acceptable output for your sample inputs, what you would consider to be "close enough" (for example, whether you consider equality to within 3 decimal places to be "close enough"), error margins or tolerances, or other ways of evaluating the outputs, for cases where someone else does not get identical outputs when using your sample data.

In the same way that it is expected that others cite your papers if they have used them within their research, you can request that others cite your software. This helps you to get credit for your research as manifested in your software. You can search for these citations in papers, publications, other software, documentation, web pages and blog posts and so gather information relating to impact of your software. This can help you to demonstrate the impact of your software and its contribution to research to your employers, your community and your funders.

Provide a CITATION.cff file with your citation expressed in the Citation File Format (CFF) 20 21. CFF is a structured format for citation files, which allows such files to serve as both a human- and machine-readable description of your recommended citation.

Metadata is information about your software. This can include programming language, operating systems, software type, authors, funders, licence and related research objects to name but a few. Metadata can both help digital repository managers categorise and index your software deposit and to help other researchers find your software according to criteria of relevance to them. However, some digital repositories are limited in the metadata they record, via their submission forms or APIs. Repository hosting services can also be limited in terms of the metadata they provide, which can limit the effectiveness of software deposit tools such as the figshare-GitHub integration 22 or Zenodo-GitHub integration 23.

Provide a codeMeta.json file with your metadata expressed in the CodeMeta schema 24. CodeMeta is a structured format for software-related metadata and is both human- and machine-readable.

A comprehensive deposit includes everything in a minimal and runnable deposit but provides a richer set of documentation and includes test code and additional test and other sample data. A comprehensive deposit allows other researchers to reuse, customise and modify your software and provides documentation allowing them to understand, in detail, both how your software implements your research and where it sits in its wider software ecosystem.

If you want others to customise your software, you need to document how they can do this. You need to provide developer documentation. Documentation for developers can include: how to set up a development environment to build, test, modify and extend the software; how to run any tests; step-by-step lists of how to run any manual tests and how to interpret the outputs; information on any application programming interfaces (API) 25 supported by your software; descriptions and diagrams of the design of your software; and the rationale as to why it is as it is.

It can help others if you complement your source code with a pseudo-code 26 narrative of what it does and how it does it. This narrative can bridge the gap between your research in the abstract, as, for example, described in papers, and your research as concretely implemented in your source code. It can help others understand how you implemented your research without needing to understand the specific programming language in which you implemented it. As for source code, a pseudo-code narrative can include citations for publications describing algorithms or analyses that have been implemented, or used, by you.

Research software does not exist in a vacuum, but forms a part of an ecosystem, which includes the sources – hand-crafted data, processes, services, software, databases – from which the data it consumes originates and the sinks to which the data it produces is destined. It can help others to understand how your software contributes to research and what it does, if you provide information on this ecosystem.

You can use an English language narrative to describe this ecosystem. In addition to this, Research Object ontology 27, Common Workflow Language (CWL) 28, GA4GH Task Execution Schema (TES) 29, Workflow Description Language (WDL) 30 and YAWL (Yet Another Workflow Language) 31 all offer ways to more formally represent software, processes, parameters, inputs, outputs and the relationships between these.

Source code for test cases can be a valuable complement for your source code, as these provide concrete examples of how your functions and components are used and the expected outputs for your test inputs.

In a comprehensive deposit, you might want to include a richer set of sample input and output data that exercises a wider range of features of your software, or demonstrates its behaviour under a greater range of conditions.

Related Software deposit guides:

Deposits:

Comments, readability and documentation:

Copyright and licences:

CodeMeta and codeMeta.json files:

Software citation and CITATION.cff files:

Depositing research data:

Please cite as: Michael Jackson (ed.) (07 August 2018). Software Deposit: What to deposit (Version 1.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1327325. Online: https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance/WhatToDeposit.html.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Deposit content | Done |

|---|---|

| Minimal deposit | |

| Simple README | |

| Copyright and licence(s) (LICENCE, licences/) | |

| Authors and other contributors (CONTRIBUTORS) | |

| Source code | |

| Runnable deposit | |

| Comprehensive README | |

| User documentation | |

| Dependencies documentation | |

| Sample input and output data | |

| Recommended citation (CITATION.cff) | |

| Metadata (codeMeta.json) | |

| Comprehensive deposit | |

| Developer documentation | |

| Narratives of what the code does and how it does it | |

| Narratives of the software's ecosystem | |

| Test code | |

| Additional sample or test data |

The Software Sustainability Institute, https://www.software.ac.uk.↩

Jisc, https://www.jisc.ac.uk.↩

"README", Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/README.↩

ORCiD, https://orcid.org/.↩

Or LICENCE, LICENCE.txt, LICENSE.txt, LICENCE.md or LICENSE.md.↩

Docker, https://www.docker.com/.↩

Singularity, http://singularity.lbl.gov/.↩

"Virtual machine", Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_machine.↩

Digital Object Identifier (DOI), https://www.doi.org/.↩

Archival Resource Key (ARK), J. Kunze and R. Rogers (2008) The ARK Identifier Scheme, California Digital Library and US National Library of Medicine, May 2008. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p9863nc.↩

PyPA pip, https://pip.pypa.io/en/stable/.↩

Apache Maven, https://maven.apache.org.↩

RubyGems, https://rubygems.org/.↩

"1.1.1 The DESCRIPTION file", Writing R Extensions, version 3.5.0 (2018-04-23), https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/R-exts.html#The-DESCRIPTION-file.↩

Ansible, https://www.ansible.com/.↩

Vagrant, https://www.vagrantup.com/.↩

"The FAIR Data Principles", FORCE 11, https://www.force11.org/group/fairgroup/fairprinciples.↩

For example, CodeMeta, https://codemeta.github.io/terms/, provides a "supportingData" term; figshare, https://figshare.com/, provides a "references" field; and, Zenodo, https://zenodo.org, provides a "relatedIdentifiers" property.↩

For example, in a number of versions of Python, 0.1 + 0.2 gives the result 0.30000000000000004!↩

Citation File Format (CFF), https://citation-file-format.github.io/. A machine-readable approach to specifying the citation that others should use when citing your software.↩

Smith A.M., Katz D.S., Niemeyer K.E., FORCE11 Software Citation Working Group. (2016) "Software Citation Principles". PeerJ Computer Science 2:e86. doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.86. https://www.force11.org/software-citation-principles.↩

"How to connect figshare with your GitHub account", figshare knowledge, https://knowledge.figshare.com/articles/item/how-to-connect-figshare-with-your-github-account-1.↩

"Making your code citable", GitHub Guides, https://guides.github.com/activities/citable-code/.↩

The CodeMeta Project, https://codemeta.github.io/. A machine-readable approach to documenting software metadata. Specific CodeMeta terms are listed at https://codemeta.github.io/terms/.↩

"Application programming interface", Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Application_programming_interface.↩

"Pseudo-code", Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudocode.↩

Soiland-Reyes, S. and Bechhofer, S. (eds.) (2016) "Research Object ontology", 1.0.0-SNAPSHOT, 28 January 2016, http://wf4ever.github.io/ro/2016-01-28/.↩

Common Workflow Language (CWL), http://www.commonwl.org.↩

GA4GH Task Execution Schema (TES), https://github.com/ga4gh/task-execution-schemas.↩

Workflow Description Language (WDL), https://software.broadinstitute.org/wdl/.↩

YAWL: Tet Another Workflow Language, http://yawlfoundation.org/.↩