|

|

Version 1.0

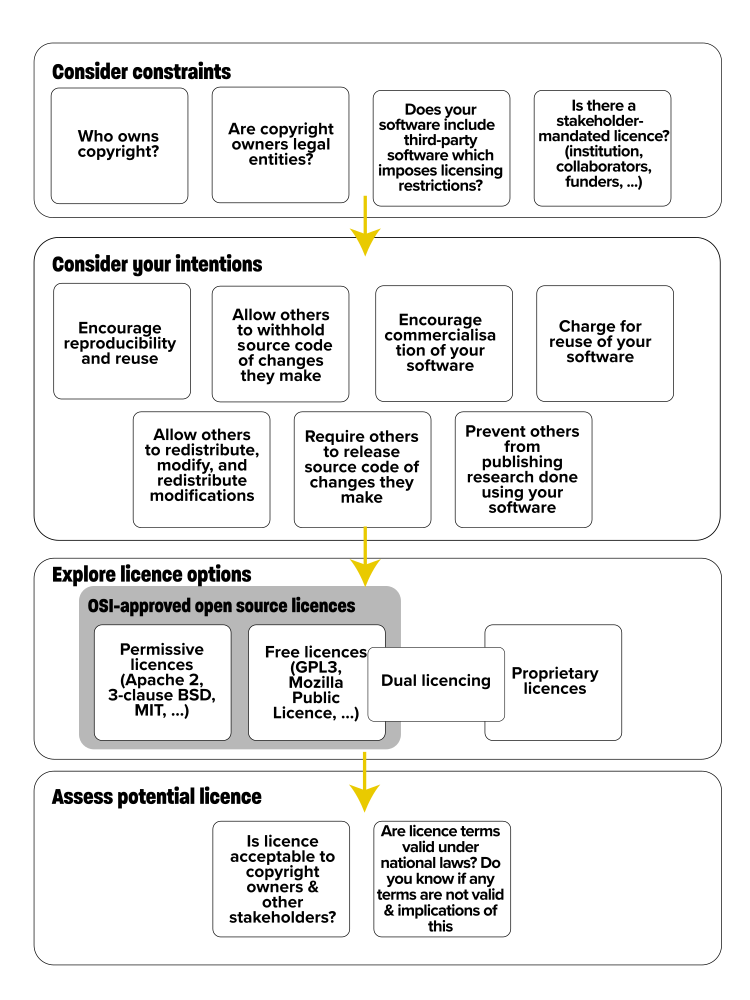

By depositing your software into a digital repository, you are implicitly stating that, at some point in time, you expect, or hope, someone will download it, with the aim of inspecting, replicating, reproducing or reusing your research. A software licence is an explicit, and legally-binding, statement of what others can, and cannot, do with your software and any obligations upon them. This guide provides an overview of the licensing options available - specifically open source licences, proprietary licences and dual licencing - and the key qualities of each in respect to allowing others to inspect, use and reuse your software.

How to choose a software licence

This guide is one of a series of guides on software deposit, written by The Software Sustainability Institute 1, funded by Jisc 2. For an overview of the series, see Michael Jackson (ed.) (07 August 2018). Software Deposit: Guidance for Researchers (Version 1.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1327310. Online: https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance/SoftwareDepositGuidance.html.

Jisc's guide to "Intellectual property law" 3 defines intellectual property rights (IPR) as "rights granted to creators and owners of works that are the result of human intellectual creativity." One such right is copyright, defined by Jisc's guide to "Copyright law" 4 as "a legally enforceable property right that enables a rights holder to profit from a work such as a book, for example. It does this by preventing others from exploiting the work without the rights holder's say so for a period of time."

Jisc's guide to "Copyright law" defines a licence as a "a contractual agreement between the copyright owner and user that limits how the user can use the work." For software, a licence specifies the terms and conditions under which others can use, distribute and modify your software.

Binaries such as executables, Docker 5 or Singularity 6 containers or virtual machines 7 can support replicability and reuse. Depending on the implementation (e.g. how configurable they are) they may also support reproducibility. However, they do not allow others to inspect your software to understand exactly what was run and how your results were produced. A complementary paper may provide this information but the paper does not produce your results, the source code that you run does. Source code has a value even if it no longer can be compiled or run, serving as a programmatic description of the research that was done.

Publishing source code in a digital repository, or sharing it with others, does not immediately imply that the software is open source. For example, GitHub 8 states that in the absence of an appropriate licence, users only have permission to view and copy software that they host. To be considered open source, the software must be accompanied by a licence which typically allows others to view the source code, redistribute the source code as-is, to modify the source code and to distribute the source code of their modifications.

Even if your funders or other stakeholders do not require you to release your source code, then depositing your software with an open source licence should still be your de facto choice, unless there are legal, ethical or commercial concerns. Open source software gives others the freedom to inspect your software, to read its source code and understand exactly what was run and how your results were produced and to validate your results. It also supports replicability, reproducibility and reuse.

The global non-profit Open Source Initiative (OSI) 9 has produced an "Open Source Definition" 10. This promotes a shared understanding of, and a consensus around, the term "open source". The OSI use this definition, along with criteria, including the clarity and simplicity of a licence, to accredit licences, which are termed "OSI-approved". Most of the popular open source licences are OSI-approved.

If choosing an open source licence, then adopt one that is OSI-approved, has been through this community-driven accreditation process, is widely used and is well understood.

One class of open source licences are free open source licences, where free refers to freedom, not zero-cost. In essence, free open source licences allow anyone to customise or extend the source code and then release a binary of this modified code. However, they require that the source code of the changes also be distributed. Free open source licences are intended to preserve the freedom to inspect, redistribute and modify source code.

Free open source licences may deter commercial exploitation, as companies may not be willing to use software that requires them to release the source code of any modifications they make. However, they do keep the source code available, even in the presence of modifications by others.

Examples of popular OSI-approved free open source licences include GNU General Public License 3 11 and the Mozilla Public License 12.

Permissive open source licences allow anyone to customise or extend the source code and then release a binary of this modified code. However, unlike free open source licences, there is no obligation to release the source code of the changes.

Permissive open source licences can encourage commercial exploitation, as companies may be more willing to use software that does not require them to release the source code of any modifications they make. Your software could be commercially exploited but you won't get any financial benefit from it.

Examples of popular OSI-approved permissive open source licences include the Apache 2 License 13, 3-clause BSD License 14 and the MIT Public Licence 15.

Proprietary licences are commonly used by commercial vendors who wish to protect their intellectual property. A proprietary licence typically only allows use of a binary and imposes conditions on the use of this binary, for example forbidding redistribution to others or reverse engineering it, or mandating installation on one computer only, or use for specific time period or for a specific purpose. The original authors retain full ownership over their software. Source code can be released under a proprietary license too. For example, the HSL Mathematical Software Library 16 provides source code under an academic licence which forbids redistribution in source or binary form 17.

Research software, including source code, could be deposited under a proprietary licence which allows others to inspect the source code and validate your results and, possibly, also support repeatability, replicability and reuse, including commercial reuse. However, the licence could preclude them from disclosing details of the source code, modifying or redistributing it or publishing papers derived from it without your explicit consent or a fee.

If you want to commercialise your research software, but also deposit it in a digital repository, then dual licensing is preferable to a sole proprietary licence. If you are a copyright owner, you can licence your software in as many ways as you want. Dual licensing 18 is a model where software is released under both a free open source licence and a proprietary licence. For example, you could deposit your software under the GNU Public Licence. Other researchers can then inspect your source code, validate your results and reuse your software, but will be obliged to release the source code of any changes. For commercial companies who want to exploit your software, but not want to share their modification, you can sell them a proprietary licence that does not oblige them to release their modifications.

An example of dual licensed software is MIT's FFTW 19 Fourier transform library, available under both the GNU General Public License, version 2 and a proprietary licence available from MIT's Technology Licensing Office 20.

There can be many factors that can constrain both your statement of copyright and the licence you could choose. Ask yourself, and your fellow stakeholders, the following questions.

Who owns the copyright? If you are an employee of an institution or company, check your contract with your employer, since they may own the copyright on any work you do as an employee. If you are part of a collaboration, then copyright may be shared across all institutions or companies in that collaboration.

Is the copyright owner a legal entity? Copyright holders must be legal entities such as people, companies, institutions, or groups of these.

Is there a licence you are required to use? Your institution, company, funder, collaborators or other stakeholders may mandate a licence you are required to use. For example, Wellcome Open Research require an open source licence and strongly recommend an OSI-approved open source licence 21.

What are the licences of third-party software you have included or modified in your own software? If your software includes third-party software, either as-is or modified, then your choice of licence may be affected by the licences of that software. For example, if you modify code released under the GNU Public Licence then you are required to licence your modifications under the GNU Public Licence too and to release the source code of your modifications along with any binaries. In some cases, different licences for your own and third-party code may be incompatible 22, meaning either you need to change your licence or consider not distributing the third-party software alongside your own.

Are the terms of your chosen licence valid under your national laws? Or, do you know if any terms are not valid and the implications of this? Certain licences, or specific licence terms, may not be valid within certain countries. For example, the MIT License states that "In no event shall the authors or copyright holders be liable for any claim, damages or other liability, whether in an action of contract, tort or otherwise, arising from, out of or in connection with the software or the use or other dealings in the software." But, under German law a complete disclaimer like this is invalid 23. In contrast, the Apache 2 License has a similar statement but with the proviso "unless required by applicable law (such as deliberate and grossly negligent acts) or agreed to in writing...".

In the same way that it is expected that others cite your papers if they have used them within their research, you can request 24 that others cite the use of your software. You can search for these citations in papers, publications, other software, documentation, web pages and blog posts and other software and so gather information relating to impact of your software. This can help you to demonstrate the impact of your software and its contribution to research to your institution, your community and your funders.

The Software Sustainability Institute provide the foregoing information on an "as-is" basis, makes no warranties regarding any information provided within and disclaims liability for damages resulting from using this information. You are solely responsible for determining the appropriateness of any advice and guidance provided and assume any risks associated with your use of this advice and guidance. If you have any questions regarding the right licence for your code or any other legal issues relating to it, consult with a professional for advice relating to your individual circumstances.

If you work for a college or university, you may have a research exploitation office that can advise you on which licence to choose, which licences are valid under local laws and which might best fit your requirements. Your local research data managers, as well as collaborators, funders, or publishers may also be able to advise you.

Organisations providing information and advice about open source software:

Free online tools to help you select licences for your software:

Intellectual property and copyright:

Open source licensing:

Software citation and CITATION.cff files:

Please cite as: Michael Jackson (ed.) (07 August 2018). Software Deposit: How to choose a software licence (Version 1.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1327316. Online: https://softwaresaved.github.io/software-deposit-guidance/HowToChooseSoftwareLicence.html.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Software Sustainability Institute, https://www.software.ac.uk.↩

Jisc, https://www.jisc.ac.uk.↩

"Intellectual property law", Jisc, 2014, https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/intellectual-property-law.↩

"Copyright law", Jisc, 2014, https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/copyright-law.↩

Docker, https://www.docker.com/.↩

Singularity, http://singularity.lbl.gov/.↩

"Virtual machine", Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_machine.↩

"5. License Grant to Other Users", GitHub, https://help.github.com/articles/github-terms-of-service/#f-copyright-and-content-ownership.↩

Open Source Initiative (OSI), https://opensource.org.↩

Open Source Definition", Open Source Initiative (OSI), http://opensource.org/osd.↩

"GNU General Public License version 3", GNU, http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.en.html.↩

"Mozilla Public License", Mozilla, https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/MPL.↩

"Apache 2 License", Apache, http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0.↩

"3-Clause BSD License", Open Source Initiative, https://opensource.org/licenses/BSD-3-Clause.↩

"MIT Public License, Open Source Initiative, http://opensource.org/licenses/MIT.↩

The HSL Mathematical Software Library, http://www.hsl.rl.ac.uk.↩

"HSL Licencing", The HSL Mathematical Software Library, http://www.hsl.rl.ac.uk/licencing.html.↩

Yeates, S. (2006) "Dual licensing", OSS Watch, May 2006, http://oss-watch.ac.uk/resources/duallicence.↩

FFTW, http://www.fftw.org/.↩

"License and Copyright", FFTW, http://www.fftw.org/doc/License-and-Copyright.html.↩

"Software & source code", Wellcome Open Research, https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/for-authors/data-guidelines.↩

"Licence compatibility", Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/License_compatibility.↩

"Is the normal exclusion of liability and warranties in open-source licenses effective in Germany?", Institute for Legal Questions on Free and Open Source Software, http://www.ifross.org/en/normal-exclusion-liability-and-warranties-open-source-licenses-effective-germany.↩

"request" not "require". For a related discussion, see "Is there an open-source license that enforces citations?", Academia StackExchange, October 2017, https://academia.stackexchange.com/questions/97480/is-there-an-open-source-license-that-enforces-citations.↩